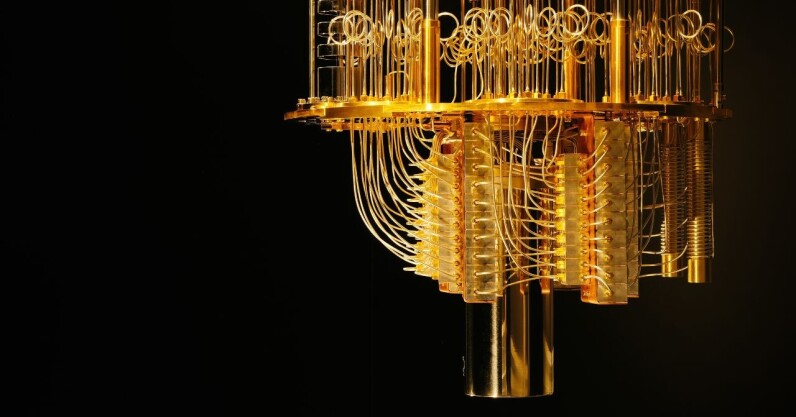

The UK’s new quantum computing missions have been praised as “visionary” and “exciting” plans that can reap financial and geopolitical benefits.

The five long-term moonshots were launched today by the British government.

The first aims to build quantum computers that can run 1 trillion operations by 2035. Another with a deadline for that year is deploying the world’s most advanced quantum network at scale. This initiative aims to pioneer the future quantum internet.

Three other projects have an earlier target date of 2030.

Get your ticket NOW for TNW Conference – Super Earlybird is 90% sold out!

Unleash innovation, connect with thousands of tech lovers and shape the future on June 20-21, 2024.

One plans to provide quantum sensing-enabled solutions to every local National Health Service organisation, for use in early diagnosis and treatment of chronic illnesses.

The second intends to equip aircraft with quantum navigation systems. The third aims to unlock new situational awareness with mobile, networked quantum sensors. This would be integrated into critical infrastructure.

Startups and investors welcomed the ambitious plans.

“The missions are bold and contain some genuinely exciting and visionary thinking,” said Stuart Woods, COO of Quantum Exponential, a VC fund and accelerator for the sector.

“The plan to implement quantum technology wide scale in the NHS to save money is particularly welcome and our expertise in medical quantum sensing is already world-class — this could greatly accelerate point-of-care diagnostics.”

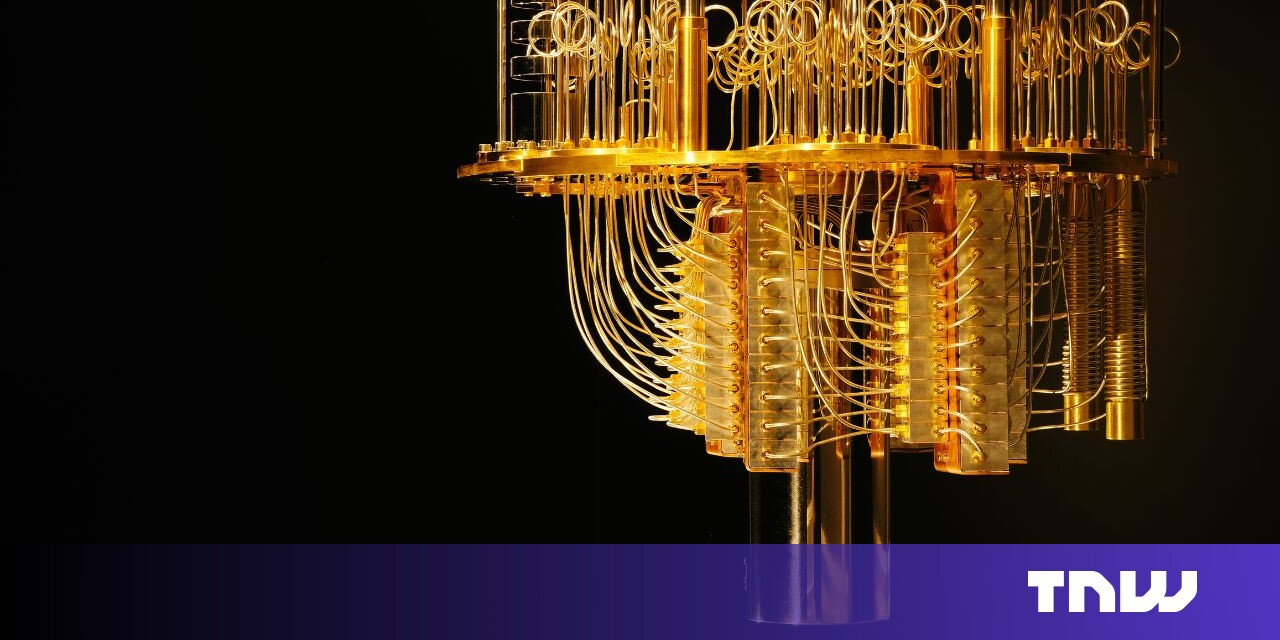

Analysts have also pointed to the economic benefits. According to McKinsey, quantum computing could create $1.3 trillion ($1.2 trillion) in value by 2035. To maximise its share of that money, the British government is taking a targeted approach.

“The UK can’t outspend the United States, China or the European Union,” Steve Brierley, the CEO of quantum startup Riverlane, told TNW.

“As a nation, we’re unlikely to even outspend some of the US and China’s individual technology giants. But with a focused approach as outlined today, the UK quantum computing industry can work to solve the scaling problem for all quantum computers globally.”

The politics of quantum computing

Not everyone is a fan of the plans. Critics argue that governments should minimise their direct involvement in technological development. Instead, they want politicians to focus on fostering the broader investment environment, by providing tax incentives and improving infrastructure.

Brierley would like both forms of support. He points to the examples set in the US, where the government has built NASA for aerospace advances, IARAP for intelligence technologies, DARPA for defence tech, and national labs for supercomputing.

The impact of these bodies has spread far beyond their founding missions. They’ve introduced innovations ranging from GPS and smartphone cameras to a little something called “the internet.”

“Emerging technologies with enormous potential often first need public seed investment to take it from development to commercial stages,” Brierley said. “If done right, early government investment can unlock industries worth billions in the long-term as well as geopolitical advantage.”

That investment, however, remains a concern. Funding for the new missions will reportedly come from the £2.5 billion (€2.86bn) that was previously committed to a 10-year national quantum strategy. Woods believes the ambitious missions will need a bigger cash injection.

“While it’s encouraging to see a commitment from the government across the spectrum of quantum technologies, it is simply not practical for the UK to strive for ‘world-leading’ status in such a range of deep technologies with a £2.5bn, inadequately defined national quantum strategy,” he said.