Two spacecraft have taken a giant leap towards explaining the Sun’s engimatic heat.

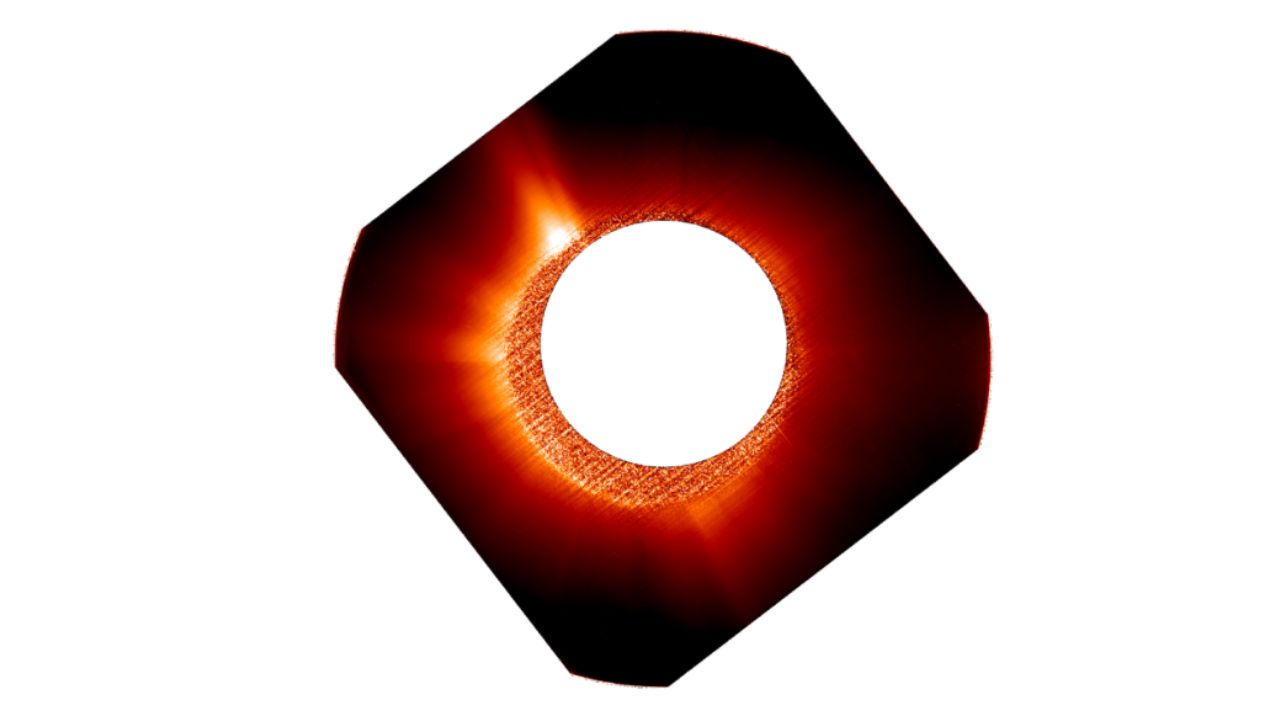

The collaboration between NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) explored an enduring mystery. In theory, the sun’s atmosphere — the corona — should be cooler than its surface. This is because the Sun’s energy comes from the nuclear furnace in its core. As the corona is further away from this heat source, logic should dictate that it’s cooler.

In reality, that’s not the case. The sun’s surface is “only” around 6,000 degrees Celcius. The corona, meanwhile, is a whopping 1 million degrees — over 150 times hotter.

To explain the divergence, scientists point to an electrically charged gas known as plasma, which comprises the corona. They suspect that turbulence in the solar atmosphere is heating the plasma, but have struggled to prove the theory.

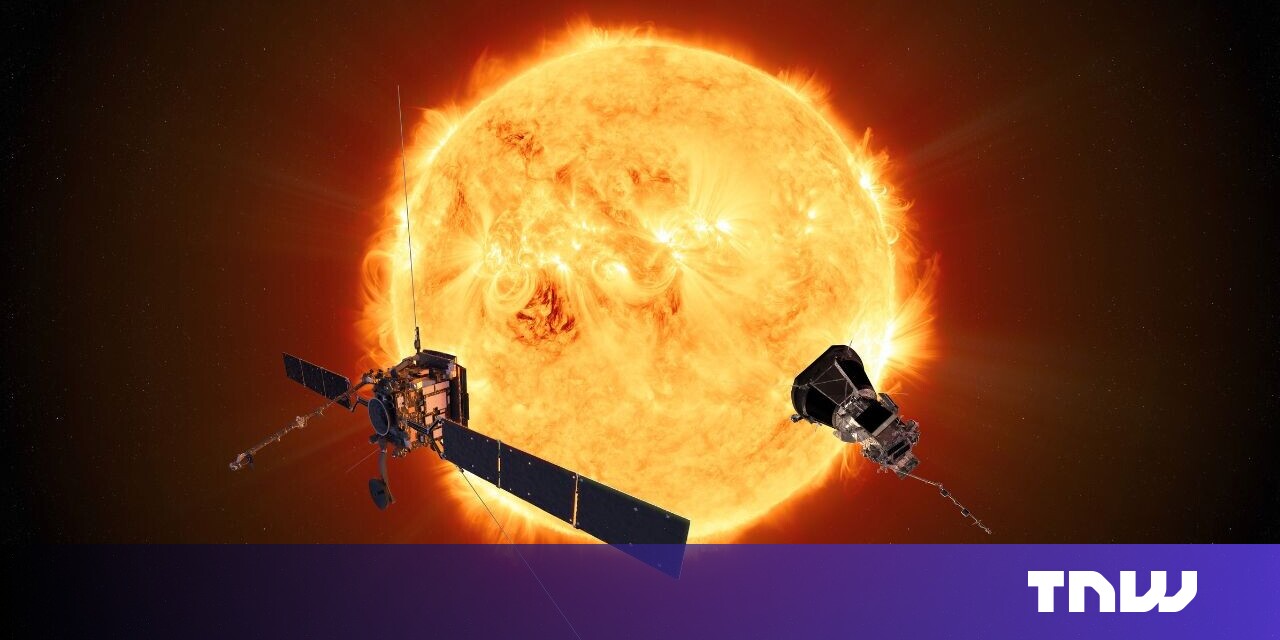

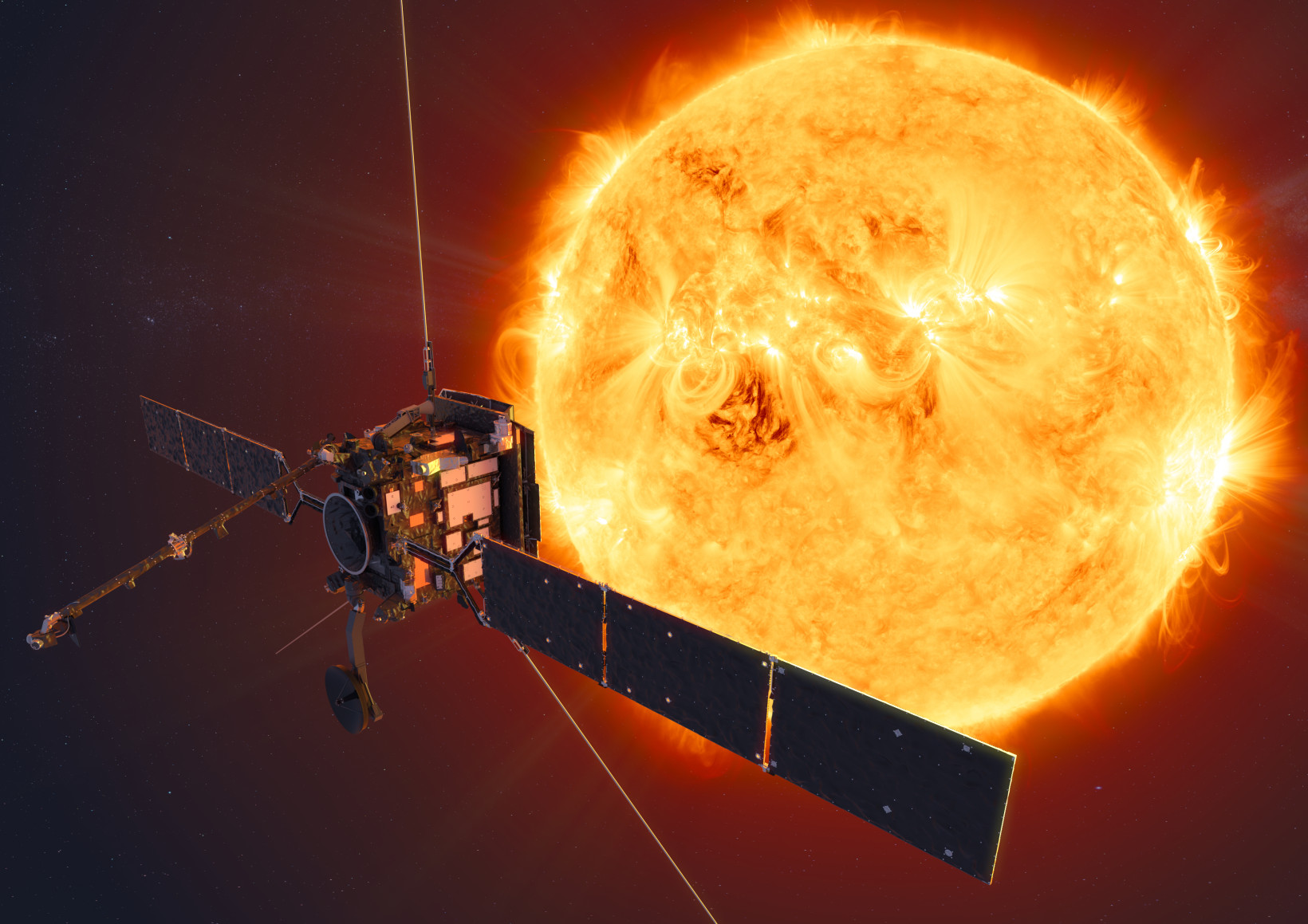

To gather further evidence, two spacecraft were needed. One would conduct remote sensing at a certain distance away from the target. It would then use cameras to observe the Sun and its atmosphere at different wavelengths.

AI: How can businesses safely optimise its potential?

Surround yourself with the information, inspiration and people who are sharing their strategies for a world transformed by crisis. Join the Financial Times and TNW at The Global Boardroom, 8-10 November.

The other spacecraft would fly through the region. As it moved, the satellite would take measurements of particles and magnetic fields in the area.

Alone, each spacecraft could unearth useful clues. But together, they could paint a fuller picture of what’s happening in the plasma.

NASA and the ESA had the ideal candidates for the mission: the Solar Orbiter and the Parker Solar Probe.

The ESA-led Solar Orbiter was primarily assigned remote sensing operations. NASA’s Parker Solar Probe, meanwhile, was tasked with getting even closer to the Sun to conduct in-situ measurements.

Together, the two spacecraft achieved an interstellar milestone: the first simultaneous measurements of the large-scale configuration of the solar corona and the microphysical properties of the plasma.

The researchers revealed their findings in a study paper published this week in Nature Communications.

After comparing the observations, the research team became convinced that turbulence was a method of transferring energy. They compare the effect to stirring a cup of coffee. When the fluid is moved, energy is transferred to increasingly smaller scales, which eventually converts the energy into heat.

In the solar corona, the fluid is also magnetised. As a result, magnetic energy can also be converted into heart.

ESA’s project scientist for the Solar Orbiter, Daniel Müller, hailed the research findings.

“This is a scientific first,” Müller said in a statement. “This work represents a significant step forward in solving the coronal heating problem.”

Further work is still needed to demystify solar heating, but we now have the first measurement of the process.