Ronald D. Moore is something of a legend in sci-fi circles, having written numerous episodes of Star Trek: The Next Generation and Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, and serving in producer roles for both shows. In 2003, he went on to create and showrun the re-imagined Battlestar Galactica series.

His latest project is the Apple TV+ series For All Mankind, which depicts the space race in a wildly different alternate reality. With the fourth season underway now, we caught up with the series creator about the show’s view of life on Mars, his optimistic take on sci-fi, and where the story may go from here.

What’s the elevator pitch on For All Mankind for folks who haven’t been watching?

The show is an alternate history, first and foremost, of the space program. And also an alternate history of the last 50 years or so. It starts with the Russians beating the Americans to the Moon in 1969.

And as a result, everything changes. America is shocked and angered. And they decide to go all in on the space program, instead of what happened in real life where we…really, really dialed back the ambitions that NASA had to build Moon bases, go to Mars and so on.

And the next thing you know, there are women astronauts more than a decade before that happened in the US. And we have a Moon base in the mid-70s. And everything changed…the world becomes a different place, a better place [because of] the giant investment in space and space technology.

There are still problems and things to overcome. But the show says that if we had kept going in the space program, this is kind of the path that we would have been on. This is the road that [could get] you to a Star Trek-like future, an optimistic place where we solve humanity’s problems and we reach out into the cosmos in a greater spirit of celebrating our common humanity.

Many of your shows seem to be about the balance of idealism versus reality. Do you believe more strongly in one vision of the future or another?

Yeah, I think that’s a fair way to look at the work I do. And I tend to be an optimist. I try to take an idealistic view of what I hope the future is. And that worldview was definitely informed by growing up as a Star Trek fan, you know, that was a future I wanted. There was a future I eagerly believed in, and it’s still near and dear to my heart.

When you look around science fiction, generally speaking, anything in the future is, like, dystopian. The future always sucks! I love Blade Runner, I love Alien. But I don’t want to live in those places. Star Trek is one of the few pieces that ever said, “Hey, you know what? It’s going to work out. We’re going to figure it out. And things will get better. It may not be easy, it might be a rough road from here to there. But eventually, it’s going to be great.”

And that was an inspiring vision of science fiction for me growing up, and I still retain that. So in the projects I do, I try to retain that optimism. People are still people, and we still bring all of our human flaws with us as we reach out into space and for all mankind. And the show is chock full of all kinds of misunderstandings and bad dealings. Terrible things go wrong… but there’s a spirit of uplift and a sort of an aspirational idea of what the future could be.

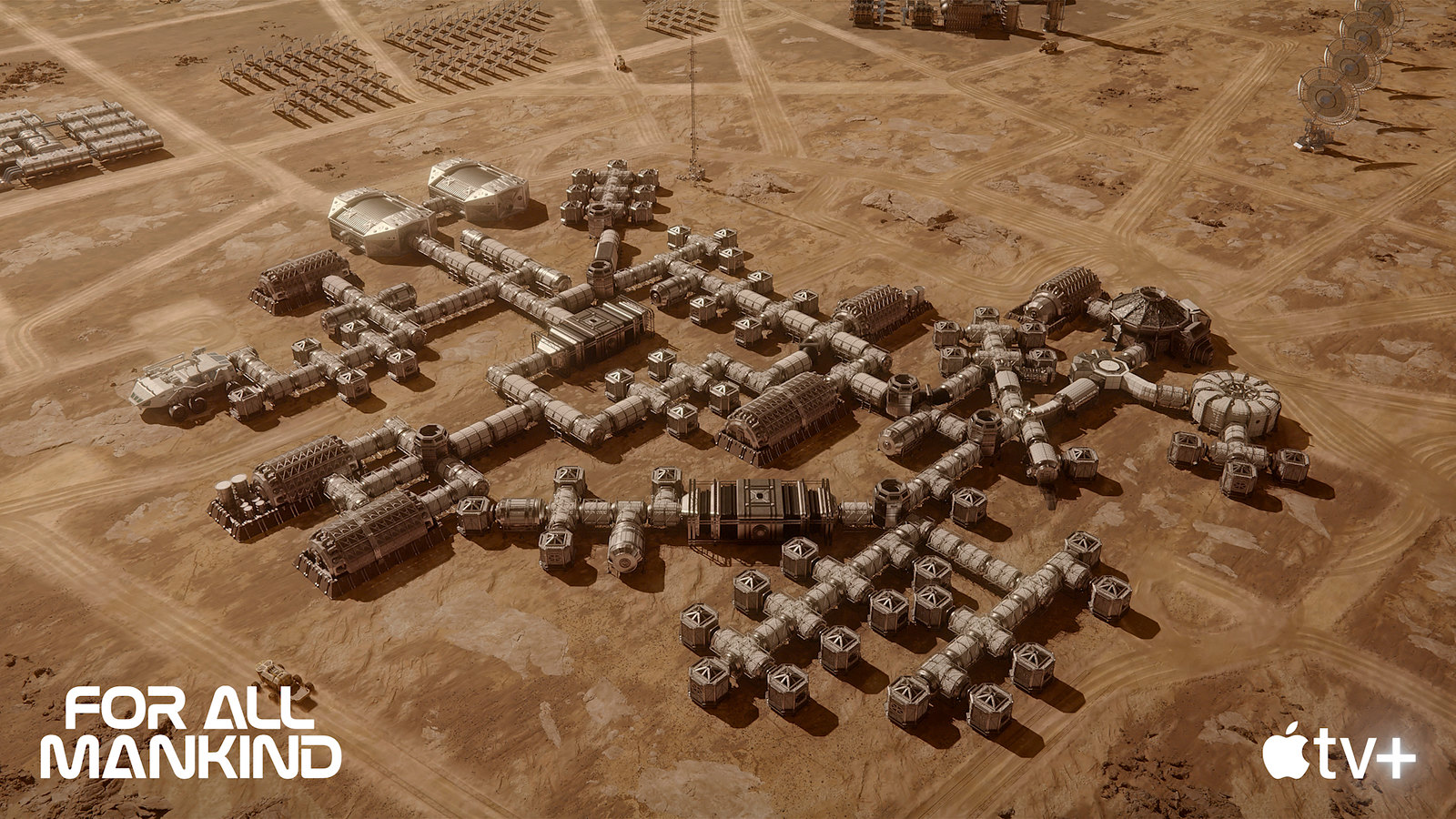

Each season of For All Mankind begins with a jump forward in time. By Season 4, humanity is settled on a Martian base and it’s expanding rapidly. Were the large time jumps always part of the plan for the series?

Yeah, they were baked into the premise. When we were developing the series. We said, “Okay, we’re gonna do the space program that we were kind of promised in the 60s and 70s.” That was the idea.

But in order to see that happen, we had to jump forward…[it lets you] really see the program expand. You see the technology take leaps and bounds. You move past the Apollo and move past the shuttle, and even move past the International Space Station. You can start developing nuclear fusion as a practical thing on Earth, you can reach out to Mars. You can see really big-scale change if you’re willing to jump ahead in the narrative, roughly a decade at a time.

The downside to that, of course, is you have characters that you become attached to who either age out of the show or die. And you have to be constantly bringing in new characters to pick up the baton. Sometimes you see children grow to adulthood and beyond, and then grandchildren, and so on.

So it becomes a generational kind of program, which is unusual. And the more we talked about it, the more exciting that possibility became, because that’s not a format that I’d seen. No one’s really done that on TV, except for a miniseries back in the 80s, Centennial. But it’s not really the way that you do an ongoing, dramatic series. So it was kind of cool to do some uncharted territory at this point in the game.

Season 3 was set in a “second space race” focused on getting to Mars. What’s the fascination with colonizing Mars, whether in our reality or the alternate reality of the show?

You know, it’s sort of there to be conquered. And I think it has a powerful draw on the imagination just for that alone. I think there is a deep part of us that wants to see what’s over the horizon, whether it’s an ocean or a mountain, and to go there. That drive, I think, is sort of eternal and very common throughout humanity.

In season four, once we got to Mars and established a settlement, now you start being able to do practical things… like possibly mining the asteroid belt, because Mars is much closer to the asteroid belt. And what are the practical realities of capturing asteroids there and actually exploiting the minerals for the benefit of life back on Earth? In addition to setting up Mars as a second home for humanity. So it does feel like there are real benefits, or potential real benefits, to be had by Mars colonization.

With problems like high radiation and limited water, Mars and space wouldn’t be great places to live. How did your team tackle the scientific realities of living offworld, and how deep did they go?

We try to go in pretty deep. We have a full-time technical consultant, Garrett Reisman, who I’ve known since the Battlestar Galactica days. Garrett was an astronaut, flew to the space station a couple of times on the shuttles…. he’s been a technical consultant on the show from its inception. Garrett is very knowledgeable about the Apollo-era space program, the shuttle era, and the future. He’s worked at SpaceX and he knows a lot of people still at NASA and is a great engineer in his own right.

He’s also put us in touch with other experts [for] each department. So there’s a great effort across the production to be as true to the real science as we can…. We are at pains to try to make the spacecraft behave like real spacecraft. We take physics seriously. You notice there’s no sound in our space, it’s the sound of the vacuum. When we come up with different engines and different methods of propulsion, we try to keep them to what could possibly happen. How would this really function? What are the challenges of doing it?

You mentioned the radiation on Mars, and on the surface of the Moon, is a real thing. We try to figure out how the astronauts would actually do that. What would be their environmental systems to keep them alive long term, and on and on and on. Everything that we’ve done, we’ve taken a great deal of time and effort to try and to make all of it, you know, at least scientifically plausible.

In season four, the romanticism of living on another planet collides with reality. What is life like for these characters on Mars?

They’re very isolated, though there are regular supply runs that come from Earth. In our future, our alternate history, we’ve improved the technology so that the trip is faster than it used to be…but it still takes months to get there. And now the population on Mars is large enough that people are starting to trade amongst themselves. There’s even a black market happening on Mars that is sort of tolerated by the powers-that-be.

But it is difficult. They are in a very harsh, unforgiving environment right outside their living modules. And spacesuits are their only way of life, if they step outside of it. In season four… there’s a two-tier system starting to develop on the surface of Mars. We have the classic astronaut types who answer to NASA and the multinational conglomerate that administers the Mars base. And then you’ve got people there who are trying to have a better life for their family, they’re trying to earn money, it’s a job. And they live in different conditions, they have different expectations, they have different working conditions, and it starts to create a conflict between the two [groups].

[We were interested in] watching that grow, from the pioneer days… and then jump ahead 10 years and see that now it’s an outpost. And what are the struggles and what are the challenges that they face as more and more people go there for different reasons, with different motives and their motivations. So that’s this sort of social crucible happening in season four.

Throughout its four seasons, For All Mankind has some fun depicting cultural moments in its alternate history. How does the writing team approach these depictions?

You know, it’s always fun at the beginning of each season. The writing staff puts on the board, all the possible things that could change in the 10-year interim. And it’s everything from big geopolitical questions — who’s president? What countries did or did not go to war with each other? — to pop-cultural things that are fun…Changing movies, who won the Academy Award and all that kind of stuff.

You start with this enormous list. And then we winnowed it down. The ideas have to fit within the narrative of what we’re doing, first and foremost. And then it becomes, alright, what’s fun? What’s too silly? So it’s an ongoing conversation that literally lasts pretty much the whole season. It takes a while for us to [be ready to create] that opening montage in the very first episode, which is the big catch-up for the audience. That takes a huge amount of work, and we tend to do it at the end of the season because some of that stuff is teasing plot elements that you’re about to see.

I read somewhere that For All Mankind was intended to run for six or seven seasons. How far into the future are you thinking about here?

Yeah, initially we had plotted out a seven-year run. And then as we got into it we said, we’re gonna be flexible about this. Maybe it’s six seasons, maybe it’s 10, we have to see how the overarching story is gonna go.

In the same way, we said it’s going to be roughly a decade jump between every season. But you know, maybe there’s a season where we don’t jump a decade…where it’s only a couple of years. Or maybe there’s a season where we jumped more than a decade. We wanted to give ourselves enough room to feel how the show would develop organically.

So yes, the plan was seven seasons, but it may or may not be seven. If you’ve multiplied that, it would be 70 years into the future, into the 2030s and 2040s. And I’m not even saying that’s for sure. That was just our general schematic of it. And each season, at the beginning, we sit down and reevaluate and see where we are in the master plan of things and whether we are still on that track? Do we want to change it? So it’s always open to conversation.

Watch the mid-season premiere of For All Mankind now on Apple TV+ with a limited-time 3-month extended trial on PS4 and PS5.

Ronald D. Moore is something of a legend in sci-fi circles, having written numerous episodes of Star Trek: The Next Generation and Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, and serving in producer roles for both shows. In 2003, he went on to create and showrun the re-imagined Battlestar Galactica series.

His latest project is the Apple TV+ series For All Mankind, which depicts the space race in a wildly different alternate reality. With the fourth season underway now, we caught up with the series creator about the show’s view of life on Mars, his optimistic take on sci-fi, and where the story may go from here.

What’s the elevator pitch on For All Mankind for folks who haven’t been watching?

The show is an alternate history, first and foremost, of the space program. And also an alternate history of the last 50 years or so. It starts with the Russians beating the Americans to the Moon in 1969.

And as a result, everything changes. America is shocked and angered. And they decide to go all in on the space program, instead of what happened in real life where we…really, really dialed back the ambitions that NASA had to build Moon bases, go to Mars and so on.

And the next thing you know, there are women astronauts more than a decade before that happened in the US. And we have a Moon base in the mid-70s. And everything changed…the world becomes a different place, a better place [because of] the giant investment in space and space technology.

There are still problems and things to overcome. But the show says that if we had kept going in the space program, this is kind of the path that we would have been on. This is the road that [could get] you to a Star Trek-like future, an optimistic place where we solve humanity’s problems and we reach out into the cosmos in a greater spirit of celebrating our common humanity.

Many of your shows seem to be about the balance of idealism versus reality. Do you believe more strongly in one vision of the future or another?

Yeah, I think that’s a fair way to look at the work I do. And I tend to be an optimist. I try to take an idealistic view of what I hope the future is. And that worldview was definitely informed by growing up as a Star Trek fan, you know, that was a future I wanted. There was a future I eagerly believed in, and it’s still near and dear to my heart.

When you look around science fiction, generally speaking, anything in the future is, like, dystopian. The future always sucks! I love Blade Runner, I love Alien. But I don’t want to live in those places. Star Trek is one of the few pieces that ever said, “Hey, you know what? It’s going to work out. We’re going to figure it out. And things will get better. It may not be easy, it might be a rough road from here to there. But eventually, it’s going to be great.”

And that was an inspiring vision of science fiction for me growing up, and I still retain that. So in the projects I do, I try to retain that optimism. People are still people, and we still bring all of our human flaws with us as we reach out into space and for all mankind. And the show is chock full of all kinds of misunderstandings and bad dealings. Terrible things go wrong… but there’s a spirit of uplift and a sort of an aspirational idea of what the future could be.

Each season of For All Mankind begins with a jump forward in time. By Season 4, humanity is settled on a Martian base and it’s expanding rapidly. Were the large time jumps always part of the plan for the series?

Yeah, they were baked into the premise. When we were developing the series. We said, “Okay, we’re gonna do the space program that we were kind of promised in the 60s and 70s.” That was the idea.

But in order to see that happen, we had to jump forward…[it lets you] really see the program expand. You see the technology take leaps and bounds. You move past the Apollo and move past the shuttle, and even move past the International Space Station. You can start developing nuclear fusion as a practical thing on Earth, you can reach out to Mars. You can see really big-scale change if you’re willing to jump ahead in the narrative, roughly a decade at a time.

The downside to that, of course, is you have characters that you become attached to who either age out of the show or die. And you have to be constantly bringing in new characters to pick up the baton. Sometimes you see children grow to adulthood and beyond, and then grandchildren, and so on.

So it becomes a generational kind of program, which is unusual. And the more we talked about it, the more exciting that possibility became, because that’s not a format that I’d seen. No one’s really done that on TV, except for a miniseries back in the 80s, Centennial. But it’s not really the way that you do an ongoing, dramatic series. So it was kind of cool to do some uncharted territory at this point in the game.

Season 3 was set in a “second space race” focused on getting to Mars. What’s the fascination with colonizing Mars, whether in our reality or the alternate reality of the show?

You know, it’s sort of there to be conquered. And I think it has a powerful draw on the imagination just for that alone. I think there is a deep part of us that wants to see what’s over the horizon, whether it’s an ocean or a mountain, and to go there. That drive, I think, is sort of eternal and very common throughout humanity.

In season four, once we got to Mars and established a settlement, now you start being able to do practical things… like possibly mining the asteroid belt, because Mars is much closer to the asteroid belt. And what are the practical realities of capturing asteroids there and actually exploiting the minerals for the benefit of life back on Earth? In addition to setting up Mars as a second home for humanity. So it does feel like there are real benefits, or potential real benefits, to be had by Mars colonization.

With problems like high radiation and limited water, Mars and space wouldn’t be great places to live. How did your team tackle the scientific realities of living offworld, and how deep did they go?

We try to go in pretty deep. We have a full-time technical consultant, Garrett Reisman, who I’ve known since the Battlestar Galactica days. Garrett was an astronaut, flew to the space station a couple of times on the shuttles…. he’s been a technical consultant on the show from its inception. Garrett is very knowledgeable about the Apollo-era space program, the shuttle era, and the future. He’s worked at SpaceX and he knows a lot of people still at NASA and is a great engineer in his own right.

He’s also put us in touch with other experts [for] each department. So there’s a great effort across the production to be as true to the real science as we can…. We are at pains to try to make the spacecraft behave like real spacecraft. We take physics seriously. You notice there’s no sound in our space, it’s the sound of the vacuum. When we come up with different engines and different methods of propulsion, we try to keep them to what could possibly happen. How would this really function? What are the challenges of doing it?

You mentioned the radiation on Mars, and on the surface of the Moon, is a real thing. We try to figure out how the astronauts would actually do that. What would be their environmental systems to keep them alive long term, and on and on and on. Everything that we’ve done, we’ve taken a great deal of time and effort to try and to make all of it, you know, at least scientifically plausible.

In season four, the romanticism of living on another planet collides with reality. What is life like for these characters on Mars?

They’re very isolated, though there are regular supply runs that come from Earth. In our future, our alternate history, we’ve improved the technology so that the trip is faster than it used to be…but it still takes months to get there. And now the population on Mars is large enough that people are starting to trade amongst themselves. There’s even a black market happening on Mars that is sort of tolerated by the powers-that-be.

But it is difficult. They are in a very harsh, unforgiving environment right outside their living modules. And spacesuits are their only way of life, if they step outside of it. In season four… there’s a two-tier system starting to develop on the surface of Mars. We have the classic astronaut types who answer to NASA and the multinational conglomerate that administers the Mars base. And then you’ve got people there who are trying to have a better life for their family, they’re trying to earn money, it’s a job. And they live in different conditions, they have different expectations, they have different working conditions, and it starts to create a conflict between the two [groups].

[We were interested in] watching that grow, from the pioneer days… and then jump ahead 10 years and see that now it’s an outpost. And what are the struggles and what are the challenges that they face as more and more people go there for different reasons, with different motives and their motivations. So that’s this sort of social crucible happening in season four.

Throughout its four seasons, For All Mankind has some fun depicting cultural moments in its alternate history. How does the writing team approach these depictions?

You know, it’s always fun at the beginning of each season. The writing staff puts on the board, all the possible things that could change in the 10-year interim. And it’s everything from big geopolitical questions — who’s president? What countries did or did not go to war with each other? — to pop-cultural things that are fun…Changing movies, who won the Academy Award and all that kind of stuff.

You start with this enormous list. And then we winnowed it down. The ideas have to fit within the narrative of what we’re doing, first and foremost. And then it becomes, alright, what’s fun? What’s too silly? So it’s an ongoing conversation that literally lasts pretty much the whole season. It takes a while for us to [be ready to create] that opening montage in the very first episode, which is the big catch-up for the audience. That takes a huge amount of work, and we tend to do it at the end of the season because some of that stuff is teasing plot elements that you’re about to see.

I read somewhere that For All Mankind was intended to run for six or seven seasons. How far into the future are you thinking about here?

Yeah, initially we had plotted out a seven-year run. And then as we got into it we said, we’re gonna be flexible about this. Maybe it’s six seasons, maybe it’s 10, we have to see how the overarching story is gonna go.

In the same way, we said it’s going to be roughly a decade jump between every season. But you know, maybe there’s a season where we don’t jump a decade…where it’s only a couple of years. Or maybe there’s a season where we jumped more than a decade. We wanted to give ourselves enough room to feel how the show would develop organically.

So yes, the plan was seven seasons, but it may or may not be seven. If you’ve multiplied that, it would be 70 years into the future, into the 2030s and 2040s. And I’m not even saying that’s for sure. That was just our general schematic of it. And each season, at the beginning, we sit down and reevaluate and see where we are in the master plan of things and whether we are still on that track? Do we want to change it? So it’s always open to conversation.

Watch the mid-season premiere of For All Mankind now on Apple TV+ with a limited-time 3-month extended trial on PS4 and PS5.