As you’re probably aware, there was a big anniversary last week. But the Mac wasn’t the only venerable Apple-related institution to hit the big four-oh on January 24. Once Steve Jobs wowed the 1984 Apple Investor Meeting at the Flint Center in Cupertino with his introduction of the original Macintosh, attendees emerged from the auditorium to be greeted by people handing out the first issue of the world’s newest computer magazine: Macworld.

Yes, it’s Macworld’s 40th as well. As you might expect from the relative health of the technology and media industries, the story of Macworld does not quite follow the same trajectory as the story of the Mac. (In the earliest days, Macworld was more successful than the Mac!)

As the person who has probably been associated with Macworld for two-thirds of its existence–I joined the staff in the fall of 1997, and I’m writing this in 2024–it’s only appropriate that I take you on a little trip down memory lane.

Making a deal with Steve

David Bunnell, founding editor of IDG’s PCWorld, was also the founder of Macworld. (The two magazines were split into separate companies later in the 1980s, only to be merged back together into a single business in the 2000s.) Bunnell, who passed away in 2016, told the story of founding Macworld a few times. But here’s the short version.

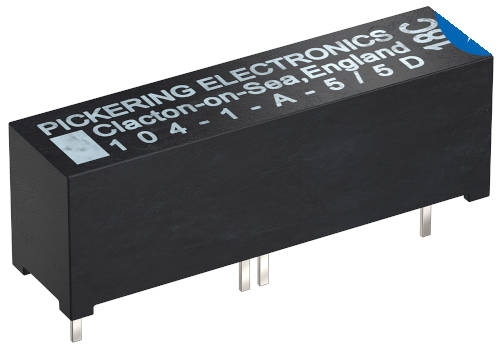

This photograph of the Mac development team (with Steve Jobs holding a Mac) appeared in the very first issue of Macworld.

Foundry

Bunnell and PCWorld colleague Andrew Fluegelman were a bit bored by the once-exciting world of personal computing settling down into a bit of a rut, thanks to the growing dominance of the IBM PC. Bunnell approached Apple about publishing an Apple II magazine, only to be told that Apple had cut a deal with fierce rival Ziff-Davis that gave them exclusive access to new Apple II buyers.

Turns out that a fortuitous conversation with Bill Gates is, in part, responsible for the founding of Macworld. Bunnell recalled that Gates had spilled the beans about Apple’s new Macintosh project a few months earlier, raving about how the Mac would change everything. So Bunnell proposed publishing Macworld, and Apple was receptive to the idea.

That might be a little too simplistic a version of the story because as Bunnell wrote, IDG founder Pat McGovern was down on Apple and wanted to launch a new magazine about IBM PC home spin-off the PCjr. Steve Jobs, meanwhile, wanted IDG to pay for the privilege of covering the Mac–while McGovern wanted Jobs to pay IDG for the privilege of making a magazine about his computer!

(Anyone who dealt with either Jobs or McGovern during their lives will recognize the attitude and sheer chutzpah on display. During a single day in 2004, I had one-on-one conversations with both of them. That was one heck of a day.)

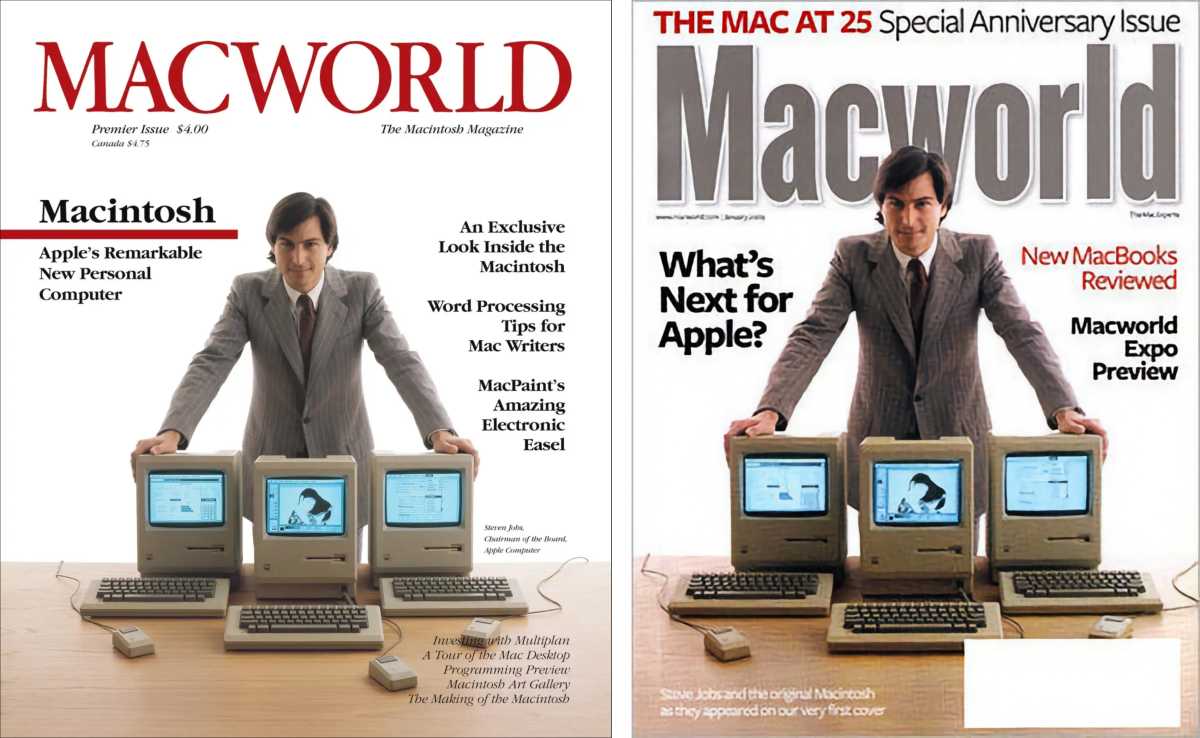

The first cover of Macworld was recreated in a special edition for the Mac’s 25th anniversary in 2009.

Foundry

While the negotiation and bickering continued, Bunnell and Fluegelman assembled a staff to build the first issue of Macworld in secret. The magazine had unfettered access to the Mac team’s offices on Bandley Drive in Cupertino. Jobs posed for the cover of the first issue, an iconic shot by photographer Will Mosgrove. (When I was editor in chief, in late 2008 we worked with Mosgrove to clean up and reprint that image for the 25th anniversary cover of Macworld.)

By this point, Macworld had so much momentum that nobody–not even Jobs and McGovern–could stop it. And so that first issue, packed with insider information about how the Mac was made, as well as reviews of the first Mac apps, was handed out on launch day. By the fourth issue, even McGovern couldn’t deny that Macworld was here to stay.

The middle years

If you read any of Bunnell’s remembrances of the founding of Macworld, you will discover two things: his immense respect for Fluegelman, who died tragically young, and that he actually wasn’t much of a fan of what the Mac became. (He was, I would argue, a PC guy through and through.)

By the early 1990s, the Mac had grown and evolved without many of its key players. Jobs was gone from Apple, and Mac models proliferated as the company fought to keep a foothold of users during the rise of the Microsoft-Intel juggernaut. Mac magazines also proliferated: The U.K.’s MacUser magazine was licensed by Ziff-Davis, PCWorld’s rival in the U.S. and the competition was on.

The last issue of MacUser, Macworld’s main competitor, was the October 1997 issue. IDG’s Macworld and Ziff-Davis’ MacUser merged that year.

Ziff-Davis

This is where I come into the story. In the summer of 1993, I was an intern at MacUser, and shortly thereafter, I was hired by editor-in-chief Maggie Cannon (formerly the editor of that Apple II magazine that blew up David Bunnell’s plans!) to become a full-time editor. Unfortunately, Apple’s slide toward bankruptcy picked up speed with the release of Windows 95, which popularized a Mac-like interface–and made it awfully hard for the real Mac to compete.

It got so bad that the two rivals, IDG and Ziff-Davis, decided that the Mac market wasn’t worth fighting over. They would regret this decision almost immediately, but not before large portions of the Macworld and MacUser staff were laid off, and the two magazines were merged into a single, larger version of Macworld.

You’d think that two sets of San Francisco-based editors who spent their professional lives covering Apple computers would be more alike than not, but the culture of the two magazines couldn’t have been more different. It took a year and a huge amount of staff turnover for the magazine to stabilize.

Funny thing about that year: It’s also the year Apple came roaring back, with Steve Jobs unveiling the iMac, a new Power Mac, and stylish new PowerBooks. All of a sudden, Apple was fun to write about again–and almost every month, there was a new product that let us produce big feature stories backed by photographic covers of great-looking Apple products.

The July 1998 cover of Macworld featured the iMac that revitalized Apple.

Foundry

The digital era

Before I even left college, I published a magazine that was entirely distributed via the internet. So when I got into traditional publishing–electronic publishing was not a viable career option in 1994–I began to try and drag the places I worked for into the modern era by suggesting we launch websites. (I was told by one person at Ziff-Davis Publishing that “the future is on CompuServe.” I’ll never forget it.)

It’s not news to say that print magazines were slow to embrace the web. In the early days, it was hard to understand how a company would ever make money on it, and print advertising was incredibly profitable. But over time, we got better at publishing to the web, as well as putting the words of notable web writers such as John Siracusa and John Gruber in front of print readers for the first time.

You know that famous line about going bankrupt slowly at first and then suddenly? For a surprising number of years, the print magazine business was still profitable–until it suddenly wasn’t. Despite good support from paying subscribers, the bottom dropped out of the print advertising market–in the case of PCWorld, it literally happened in a single month–and it overturned the economics of publishing.

The truth is, the Macworld (and PCWorld) readership was always years ahead of the general media audience in their habits. We stopped putting ink on paper and turned entirely digital back in 2014, but our audience–on the web and in our digital edition–was way ahead of us.

I left the Macworld staff in 2014, writing an editor’s column about saying goodbye to print that was also secretly my farewell to Macworld. But Macworld continued on, and so did I. By my count, I’ve written nearly 500 of these columns for Macworld in the nine years since I left!

The story goes on–for me and for Macworld. The form has changed (a lot), but the thing that David Bunnell started more than 40 years ago is still making an impact.