Experts estimate around 60% of buildings that will exist in 30 years’ time have yet to be built. This equals constructing a city the size of Stockholm every week until 2050. However, the construction sector currently doesn’t have the people or the skills to deliver the infrastructure and homes we need at the pace required. But what if we could offload some of the work to robots?

Enter 3D concrete printing — an emerging technology that uses 3D printers to create all manner of structures, from bridges and sculptures to houses and even whole neighbourhoods. These huge printers work much like their desktop equivalents, but instead of using ink, they extrude concrete. A giant robotic arm deposits the concrete layer by layer, like a tube of toothpaste, according to plans laid out in a digital blueprint.

This application of 3D printing technology has caused quite a stir in recent years, captivating millions on social media. Just take Aiman Hussein, director of printing at US-based startup Alquist 3D. His TikTok videos of 3D concrete printers building homes have racked up tens of millions of views and scored him over 60K followers.

@thelayerlord Getting ready for live printing at #ibs2022 with @blackbuffalo3d #3d #3dcp #oddlysatisfying #3dprinting #orlando #foryou #concrete #affordablehousing

♬ Tokyo Drift – Xavier Wulf

But while the process of a robot depositing layer after layer of smooth concrete might be mesmerising to some, the real buzz around 3D concrete printing is in its potential to make construction faster, cleaner, and greener.

Building better

Construction is one of the oldest professions on earth and is vital to our everyday lives: it builds the houses we live in, the infrastructure we travel on, and the schools our children learn in. But, the sector is plagued by cost overruns, chronic inefficiencies, and labour shortages. What’s more, it has a gargantuan environmental impact — the built environment is responsible for almost 40% of global CO₂ emissions and accounts for a third of all waste generated in the EU.

“If we are to deliver the homes and infrastructure we so desperately need over the coming decades — in a way that is sustainable and cost-effective — something drastically needs to change,” Rob Wolfs, professor in structural engineering at the Eindhoven University of Technology (TU/e), tells TNW.

Wolfs is one of the foremost global experts on 3D concrete printing. “This technology can help tackle some of the greatest challenges facing the construction industry today,” he says, as we zip down the escalator into the basement of TU/e’s built environment department.

Located down a narrow concrete stairwell behind a set of wooden doors is the department’s R&D lab. It smells like sawdust, fresh concrete, and potential. This is where bright ideas go to get tested and validated. It’s also home to the university’s very own 3D concrete printer. For almost a decade, the printer (which sadly doesn’t have a cool nickname) has been used to refine and develop 3D printing technology and has laid the foundation of knowledge for many of the commercial-scale projects we see today.

3D printing offers the ability for mass customisation that was previously too challenging or costly to achieve using traditional methods. Want to create a bespoke house design or a unique building component or even an artificial coral reef with complex twists and shapes? 3D printing offers that freedom of design. “You can really make everything unique, everything optimised, tailored to a specific application,” says Wolfs.

But crucially, because 3D printing is an “additive” process, building a product layer by layer, it can build structures using only the exact amount of material required. Numerous studies have shown that 3D printing in construction can reduce waste by 30-60%.

The efficiency of the process also means less concrete is needed overall: Finnish startup Hyperion Robotics claims that its 3D printing micro-factories can reduce concrete use by 75%. If concrete were a country it would be the third largest emitter of CO₂ — so the less we use it the better.

“Robots do the hard work, so you don’t have to.

3D printing automates many of the tough tasks involved in construction, such as bricklaying, reducing the number of people needed on site. Given the chronic lack of workers entering the industry, many consider automation and robotics to be the only solution to delivering the infrastructure we need at the pace and scale required.

“Robots are not going to take people’s jobs,” says Wolfs. “They’re going to do the dirty, hard labour, freeing up people to do safer, more skilled work.”

Automation also increases speed and efficiency, with some 3D printing companies claiming they can print the entire structure of a house in 24 hours.

So 3D printing in construction has the potential to produce complex designs, boost efficiency, reduce waste, improve sustainability, and address workforce challenges. But can it deliver?

Taking shape

In 2021, Dutch couple Elize Lutz and Harrie Dekkers, retired shopkeepers from Amsterdam, became Europe’s first inhabitants of a 3D-printed house in Eindhoven. Their new home, which cost €1,400 per month to rent at the time, is the first of five houses under Project Milestone — a collaborative effort between TU/e, the government, and the construction industry to validate and scale 3D construction printing. Here’s some pics of their new abode:

Construction company Weber Beamix printed the boulder-shaped house, which consists of 24 separate concrete elements, at its facility in Eindhoven. The elements were transported by truck to the building site, bolted together and secured to the foundation, after which the roof and frames were added and the finishing touches applied — the whole process took around 120 hours. The partners aim to construct the next four houses completely onsite using one giant printer.

Weber Beamix has been working closely with TU/e for years, to bring its research to market. So far the company, a subsidiary of French construction giant Saint Gobain, has printed all manner of structures: a 30-metre-long bridge in the Dutch city of Nijmegen, a 9-metre-tall pigeon tower in Qatar, and a skate park in Eindhoven.

But that’s just a drop in the ocean. In the last couple of years, 3D-printed structures have been popping up all over the show, with some seriously ambitious projects in the works.

In 2021, Germany’s first ever 3D-printed house was unveiled in the town of Beckum. In 2022, a two-storey apartment building, also in Germany, was 3D-printed in just 72 hours by a two-person crew and is now occupied by five households. In the same year, French 3D printing startup XtreeE successfully constructed five social homes in the city of Reims.

Perhaps the world’s most ambitious 3D-printed affordable housing project is in the small town of Accrington, England. The £6m Charter Street scheme, developed by Irish architecture firm Harcourt Technologies and local social housing provider Building for Humanity, will house homeless veterans and low-income families in 46 eco-homes that can each be printed in weeks. Full planning permission has already been secured for the site, and construction is set to begin imminently.

At the time of writing, Danish manufacturer of 3D concreteprinters, COBOD, is working with humanitarian foundation Team4UA to 3D-print a school in Ukraine. Over 2,000 schools have been damaged or destroyed since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine last year, and it is hoped that 3D concrete printing can expedite reconstruction efforts.

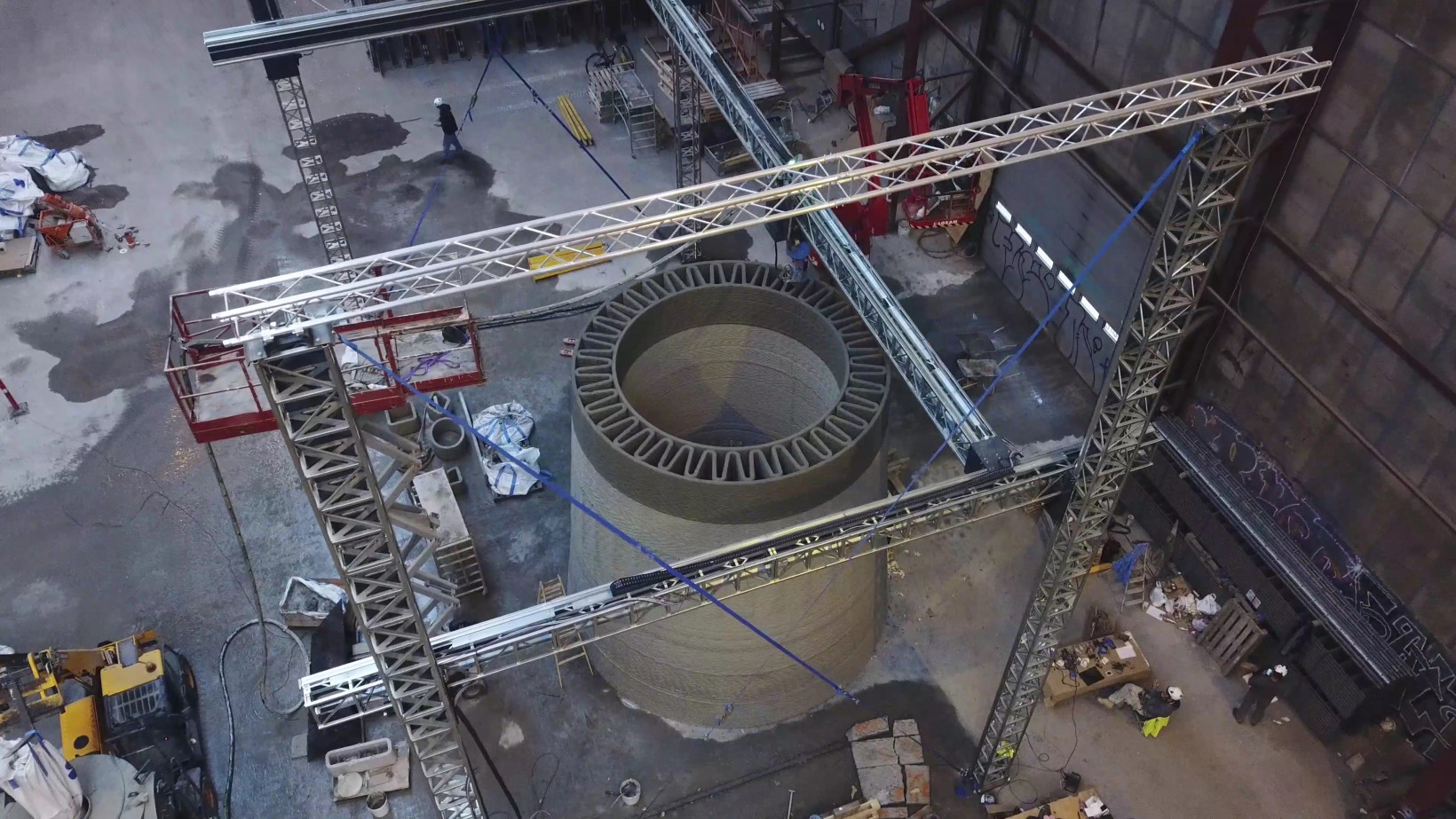

But it’s not just 3D-printed buildings that are making the headlines. The design freedom afforded by 3D concrete printers means they can create just about anything, from staircases and protective sea walls, to septic tanks and even wind turbine foundations.

According to Henrik Lund-Nielsen, CEO at COBOD, the technology can deliver its “biggest bang for the buck” not in housing but in industrial projects where reinforced concrete makes up a much larger part of the project’s total cost.

These applications are not just bound to Earth either. In December 2022, NASA awarded US startup ICON a $57m contract to develop 3D-printing technology to build roads, launchpads, and homes on the moon’s surface, as part of NASA’s Artemis program, which plans for long-term human exploration of the moon. ICON is currently developing a large 3D printer that could be transported to the moon, using lunar materials instead of concrete to print the lunar base.

More and more big players are entering the 3D construction printing space, lured by its potential benefits. COBOD, which claims to be the largest provider of 3D printers to the construction industry, is backed by a number of global industrial giants, including General Electric, which recently built the world’s biggest additive construction facility to 3D print concrete bases for wind turbines.

Yet despite the impressive progress to date, according to a recent report, there are currently only 130 completed 3D-printed buildings globally. Clearly then, the 3D printing in construction is making its mark, although its true potential is not so concrete.

Beyond the hype

“When this technology arrived on the scene around 10 years ago, people thought we were going to 3D print everything in the future — but it hasn’t quite turned out that way,” Wolfs told TNW.

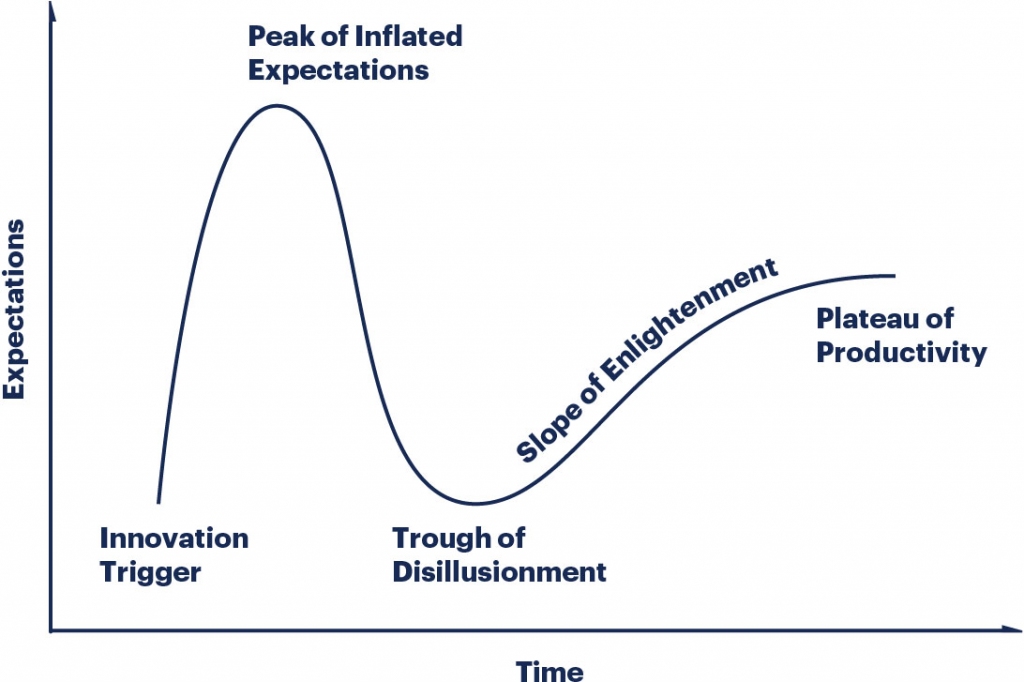

Wolfs’ insights on the development of 3D printing nod to Gartner’s Hype Cycle, which outlines the five distinct phases of a technology’s lifecycle.

As Wolfs pointed out, around 10 years ago, 3D printing as a whole was in the hype phase, or the ‘peak of inflated expectations’. Startups were popping up all over the place, VC capital was flowing, and 3D printers were expected to be busily cranking out all the tools, human organs, and automobiles anyone could ever want or need.

Then came the inevitable descent into the ‘trough of disillusionment’ somewhere around 2015 — flaws in the technology emerged, early adopters encountered performance issues, and there were low returns on investment.

Fast forward to the present day, and 3D printing as a whole appears to be on the up again, as kinks get ironed out, early adopters start to see returns, and the technology matures. However, there is a great disparity between different applications of 3D printing as to where they sit on the Gartner Hype Cycle.

“Almost all dental implants these days are 3D printed. The technology is now mainstream because it’s proven to be the best way to manufacture that product,” says Wolfs. “However, in construction, we’re not there yet, not even close.”

“3D printing won’t solve the housing crisis on its own.

Perhaps the biggest buzz around 3D construction printing lately has been its potential to solve the housing crisis. As countries worldwide face a shortage of homes, proponents believe houses that ‘can be printed in a day’ could be the solution. Wolfs is not so sure.

“3D printing won’t solve the housing crisis on its own — that issue is far too complex and is not just a technological problem,” he says. “It doesn’t make sense to replace all the traditional building methods with 3D printing either, but to find applications where 3D printing really makes sense.”

There are two key areas that could propel 3D construction printing up the ‘slope of enlightenment’, according to Wolfs: standardising the technology and making it more sustainable.

“We have to come up with ways to assess and guarantee the quality of our printed structures and move towards standardisation of this technology. It is moving so quickly it risks getting in its own way,” he said.

Will a 3D-printed home last as long as a traditionally built home? Will it be structurally sound and safe in the event of a fire or natural disaster? Since the development of the technology has outpaced updates to widely used codes and standards, it has left builders with few answers.

At TU/e, researchers are undertaking strength and material testing on a smaller scale in order to validate on a larger scale, with the idea that eventually the results will become enshrined in standards like the Euro code. For now, 3D concrete printing pioneers have to hope that their designs will pass building codes written up for structures built using traditional methods.

Then there’s the sustainability aspect. While 3D construction printing cuts waste, it still relies heavily on cement. The scaling of low-emission cement alternatives — like those infused with graphene or made from local clay — will be key to ensuring 3D printing can meet its environmental credentials.

Key to all of this is trial and error. As research advances, more projects break ground, and big players enter the industry, it seems only a matter of time before 3D construction printing can cement its place in the market.

Printing the future

Despite an apparent decade-long inertia, the digital transformation of construction is now in full swing, with technologies like Building Information Modelling (BIM), digital twins, drones, robotics, and blockchain helping contractors deliver structures more efficiently and sustainably.

Going forward, Wolfs predicts that 3D printing will become part of this ‘toolbox’ of technologies, as construction moves toward increasing levels of automation and digitisation.

As the technology continually develops, opportunities will emerge to print bigger, better, and stronger than ever before. One day, 3D printers might even be able to print multiple materials from the same nozzle, allowing the construction of not just concrete walls but steel frames, windows, and insulation, in one sweeping motion.

There is also the possibility that future structures will be printed by ‘teams’ of 3D printing robots of different sizes — one large printer for the structure, multiple smaller ones for elements like doors and windows, and swarms of flying 3D printing drones for the finishing touches.

3D printing in construction, then, is not so much of a revolution as an evolution. Either way, it seems likely that the buildings of the future will, in some part, be 3D printed.