LSD, magic mushrooms, MDMA, ketamine, DMT… it’s a suspicious product line for a legitimate business — and psychedelics startups know it. With that in mind, it’s unsurprising that the sector are wary of the stereotypes around hallucinogens.

“What the industry really needs is the most boring person in the room to be presenting the topic,” says Clara Burtenshaw, co-founder of Neo Kuma Ventures, Europe’s largest VC fund for psychedelic healthcare.

It would be harsh to call Burtenshaw the most boring person in the room, but she’s not the clichéd lover of trips. More polished entrepreneur than kaleidoscopic hippy, Burtenshaw was a corporate lawyer before pivoting to psychedelic healthcare.

It was an uncommon career switch with a familiar root: seeing loved ones struggle with their mental health. Burtenshaw thought psychedelics could provide a better remedy.

In late 2019, she cofounded Neo Kuma (Greek for “New Wave”) to invest in the treatments. Her timing proved prescient. Within weeks, the world was being plunged into a mental health epidemic.

In the first year of the COVID-19 outbreak, the global prevalence of anxiety and depression increased by 25%, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO). Already understaffed and underfunded, mental health services were pushed beyond their limits.

Inevitably, a surging demand for medications followed. But that was merely accelerating the prevailing trend. In Europe, antidepressant consumption has more than doubled in the last 20 years.

The medication can be life-saving, but the benefits aren’t equally distributed. Over a third of patients are resistant to the treatment’s mood improvements. Others can suffer from side effects, dependence, or withdrawal symptoms.

“It’s about developing the blockbuster drugs of tomorrow.

As the uptake of antidepressants soared, some researchers began to assert that they were barely better than placebos. A recent study found that 10 of the most popularly prescribed medications made a meaningful difference in only 15% of the patients who took them.

Psychedelic treatments offer an alternative. While conventional antidepressants are taken regularly over extended periods, just one trip alongside therapy can have lifelong benefits.

That transformative potential offers big business opportunities. The global mental health market was already valued at $380bn (€356bn) in 2020. By 2030, it’s projected to reach $538bn (€503bn).

The chunk that Burtenshaw’s targeting will come from psychedelic drug development — a subsector that Europe is leading.

The continent is home to some of the space’s key players, from Atai Life Sciences, a German startup that’s trialling an MDMA derivative for PTSD, to the UK’s Beckley Psytech, which recently won FDA approval to test a compound found in toads as a treatment for alcoholism. The riches, Burtenshaw hopes, will emerge after patenting the intellectual property.

“That’s how you see your return on investment,” she says. “It’s about developing the blockbuster drugs of tomorrow.”

The blockbuster drugs of tomorrow won’t be ready overnight. The process of developing, testing, licensing, and distributing new medications is a long one — but the pay-off could be enormous.

Analysts predict that the psychedelic healthcare industry will be worth $6.9bn (€6.4bn) by 2027. But before the sector reaps those rewards, it must first convince the sceptics.

Once regulators approve a drug, it moves from an illicit substance to a recognised medicine. But the route to psychedelics is long and perilous. To earn their backing, the sector needs to win clinical arguments.

“Psychedelics does attract evangelists who talk about all of the wonderful things about the treatment and perhaps gloss over the risks,” says Burtenshaw. “But we need to take a data-driven, evidence-based approach to looking at these treatments.”

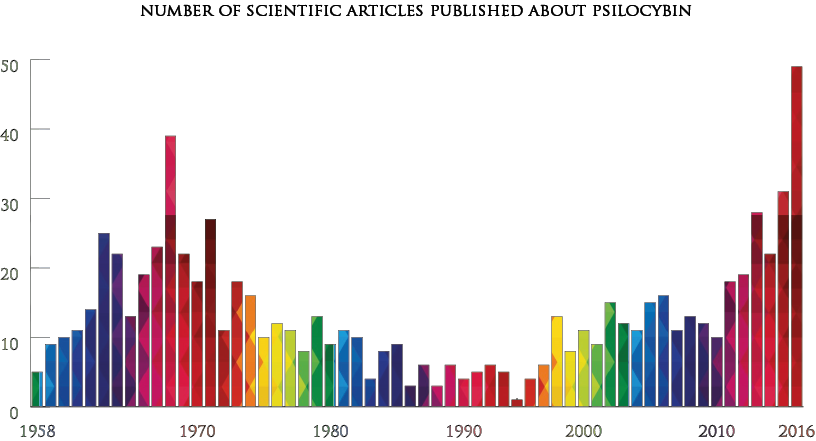

And that evidence base is growing. A growing body of research has shown that psychoactive substances can drive therapeutic breakthroughs for various mental health issues.

In one study Neo supported, veterans were given controlled doses of MDMA. Over two-thirds (68%) experienced complete remission from PTSD. The other 32% felt significant relief.

“That was completely unheard of in psychiatry — we don’t see results like that,” says Burtenshaw. “And many of these patients are veterans who had really ingrained PTSD and had been through a number of unsuccessful treatments in the past.”

Promising results have also emerged at Compass Pathways, a startup that was listed on the Nasdaq in September 2020. Based in the UK, the company has developed a synthetic form of psilocybin — a psychoactive component in magic mushrooms — for treatment-resistant depression (TRD), which is diagnosed after conventional medicine proves ineffective.

A study published last year found that the substance can significantly allay severe depression. After taking a single 25mg dose alongside psychological support, around 39% of participants were in remission by week three. Notably, the biggest impact came a day after receiving the treatment. Standard antidepressants, by contrast, take several weeks to reach maximum effect.

Both treatments are now targeting regulatory review — which would open them up to the market. Burtenshaw believes they can push psychedelic healthcare more broadly towards the mainstream.

“What we’ve seen with psychedelics is this potential for people to really understand the root cause of their trauma, directly face it head on, work with a therapist to come to terms with it, and then get on with their lives,” she says.

Like Burtenshaw, Clerkenwell Health CEO Tom McDonald isn’t the archetypal lover of hallucinogens. McDonald spent 10 years working in management consulting with big pharma before joining Clerkenwell, a British startup that runs clinical trials for psychedelic treatments.

The career change “definitely raised eyebrows from friends and family,” says McDonald.

“There’s still a lot of stigma around, but everyone in the space is trying to normalise it. And data speaks — as do emotive stories.”

Such stories are powerful tools for changing perceptions, but the most effective narratives are localised.

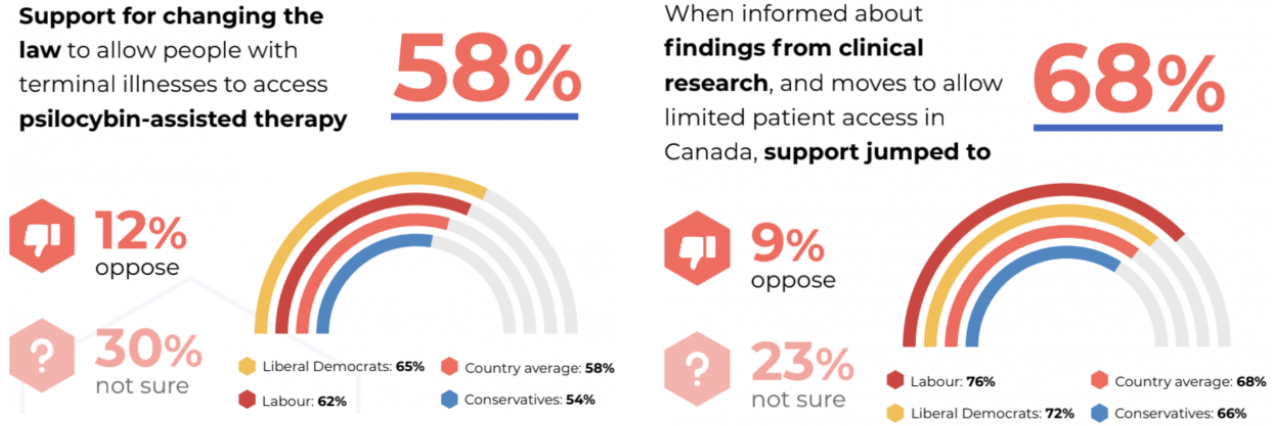

In the US, for instance, tales of military veterans using psychedelics to overcome trauma have won over sceptics. In the UK, meanwhile, the impacts on patients with terminal illnesses have garnered more public sympathy. That sympathy could bring the benefits closer to home.

Currently, most European citizens would need to travel abroad to access psychedelic therapies, but there are signs that the regional gap is narrowing.

In the UK, for instance, politicians from across the political spectrum are rallying support for the treatment. Last month, Conservative politician Crispin Blunt warned that the country’s regulation of psychedelics was “trailing behind Australia, Canada, and the United States.”

Blunt said the substances “will help address the miserable dependence of too many” on antidepressants. The veteran MP wants psilocybin to be moved from a Schedule 1 drug to the lower-risk Schedule 2, which would allow researchers to further explore its potential as a medicine.

“The science highlights their immense potential.

His plea echoes recent petitions in the EU. Just last week, a cross-party faction of lawmakers launched a new group to advance access to affordable and safe novel therapeutic applications of psychedelics in the bloc.

“Millions of Europeans are in need of better treatments,” said Czech MEP Mikuláš Peksa. “We need to ensure that novel psychedelic treatments are being considered, as the science behind them highlights their immense potential.”

That immense potential doesn’t only appeal to politicians. Relaxing rules would also create diverse openings for tech — and startups are poised to capitalise.

Europe’s psychedelics startups have already explored extensive digital applications. They range from April19’s AI drug discovery platform and Beckley Psytech’s biomarkers for tracking patients to Homecoming’s app for therapists and Wavepaths’ personalised music for treatment.

One of their most notable features is adaptability, which could extend their applications from psychedelics to the broader health and wellness markets.

With such breadth of opportunities, the sector has grounds for optimism. But startups will have to play the long game and attract patient capital.

“I think the market landscape is going to look so different in five years’ time to where it is now,” says Burtenshaw. “What we’re expecting to see is this dovetailing of destigmatisation alongside a rollout of these treatments.”

The route to market, however, appears long and treacherous. Regulatory barriers, a perilous financial landscape, and slow paths to profit have somewhat dimmed the excitement around psychedelics. But in the crucial fight for hearts and minds, the prospects of victory are growing.