AI startup Hugging Face and ServiceNow Research, ServiceNow’s R&D division, have released StarCoder, a free alternative to code-generating AI systems along the lines of GitHub’s Copilot.

Code-generating systems like DeepMind’s AlphaCode; Amazon’s CodeWhisperer; and OpenAI’s Codex, which powers Copilot, provide a tantalizing glimpse at what’s possible with AI within the realm of computer programming. Assuming the ethical, technical and legal issues are someday ironed out (and AI-powered coding tools don’t cause more bugs and security exploits than they solve), they could cut development costs substantially while allowing coders to focus on more creative tasks.

According to a study from the University of Cambridge, at least half of developers’ efforts are spent debugging and not actively programming, which costs the software industry an estimated $312 billion per year. But so far, only a handful of code-generating AI systems have been made freely available to the public — reflecting the commercial incentives of the organizations building them (see: Replit).

StarCoder, which by contrast is licensed to allow for royalty-free use by anyone, including corporations, was trained on over 80 programming languages as well as text from GitHub repositories, including documentation and programming notebooks. StarCoder integrates with Microsoft’s Visual Studio Code code editor and, like OpenAI’s ChatGPT, can follow basic instructions (e.g., “create an app UI”) and answer questions about code.

Leandro von Werra, a machine learning engineer at Hugging Face and a co-lead on StarCoder, claims that StarCoder matches or outperforms the AI model from OpenAI that was used to power initial versions of Copilot.

“One thing we learned from releases such as Stable Diffusion last year is the creativity and capability of the open-source community,” von Werra told TechCrunch in an email interview. “Within weeks of the release the community had built dozens of variants of the model as well as custom applications. Releasing a powerful code generation model allows anybody to fine-tune and adapt it to their own use-cases and will enable countless downstream applications.”

Building a model

StarCoder is a part of Hugging Face’s and ServiceNow’s over-600-person BigCode project, launched late last year, which aims to develop “state-of-the-art” AI systems for code in an “open and responsible” way. Hugging Face supplied an in-house compute cluster of 512 Nvidia V100 GPUs to train the StarCoder model.

Various BigCode working groups focus on subtopics like collecting datasets, implementing methods for training code models, developing an evaluation suite and discussing ethical best practices. For example, the Legal, Ethics and Governance working group explored questions on data licensing, attribution of generated code to original code, the redaction of personally identifiable information (PII), and the risks of outputting malicious code.

Inspired by Hugging Face’s previous efforts to open source sophisticated text-generating systems, BigCode seeks to address some of the controversies arising around the practice of AI-powered code generation. The nonprofit Software Freedom Conservancy among others has criticized GitHub and OpenAI for using public source code, not all of which is under a permissive license, to train and monetize Codex. Codex is available through OpenAI’s and Microsoft’s paid APIs, while GitHub recently began charging for access to Copilot.

For their parts, GitHub and OpenAI assert that Codex and Copilot — protected by the doctrine of fair use, at least in the U.S. — don’t run afoul of any licensing agreements.

“Releasing a capable code-generating system can serve as a research platform for institutions that are interested in the topic but don’t have the necessary resources or know-how to train such models,” von Werra said. “We believe that in the long run this leads to fruitful research on safety, capabilities and limits of code-generating systems.”

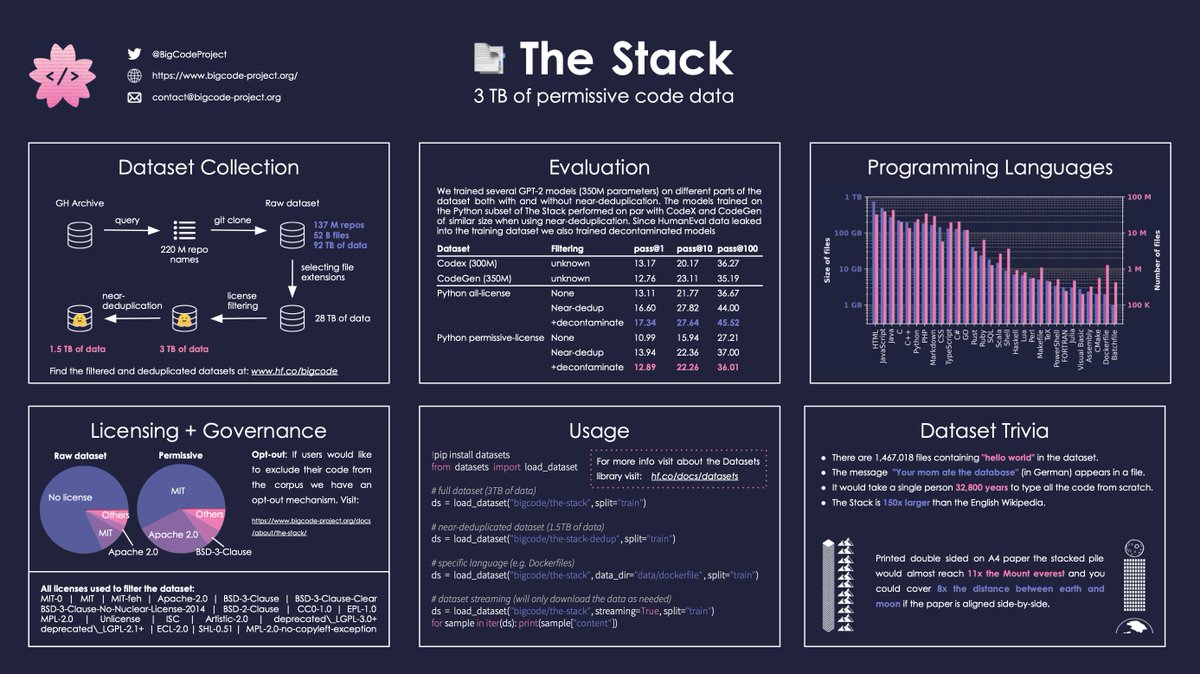

Unlike Copilot, the 15-billion-parameter StarCoder was trained over the course of several days on an open source dataset called The Stack, which has over 19 million curated, permissively licensed repositories and more than six terabytes of code in over 350 programming languages. In machine learning, parameters are the parts of an AI system learned from historical training data and essentially define the skill of the system on a problem, such as generating code.

A graphic breaking down the contents of The Stack dataset. Image Credits: BigCode

Because it’s permissively licensed, code from The Stack can be copied, modified and redistributed. But the BigCode project also provides a way for developers to “opt out” of The Stack, similar to efforts elsewhere to let artists remove their work from text-to-image AI training datasets.

The BigCode team also worked to remove PII from The Stack, such as names, usernames, email and IP addresses, and keys and passwords. They created a separate dataset of 12,000 files containing PII, which they plan to release to researchers through “gated access.”

Beyond this, the BigCode team used Hugging Face’s malicious code detection tool to remove files from The Stack that might be considered “unsafe,” such as those with known exploits.

The privacy and security issues with generative AI systems, which for the most part are trained on relatively unfiltered data from the web, are well-established. ChatGPT once volunteered a journalist’s phone number. And GitHub has acknowledged that Copilot may generate keys, credentials and passwords seen in its training data on novel strings.

“Code poses some of the most sensitive intellectual property for most companies,” von Werra said. “In particular, sharing it outside their infrastructure poses immense challenges.”

To his point, some legal experts have argued that code-generating AI systems could put companies at risk if they were to unwittingly incorporate copyrighted or sensitive text from the tools into their production software. As Elaine Atwell notes in a piece on Kolide’s corporate blog, because systems like Copilot strip code of its licenses, it’s difficult to tell which code is permissible to deploy and which might have incompatible terms of use.

In response to the criticisms, GitHub added a toggle that lets customers prevent suggested code that matches public, potentially copyrighted content from GitHub from being shown. Amazon, following suit, has CodeWhisperer highlight and optionally filter the license associated with functions it suggests that bear a resemblance to snippets found in its training data.

Commercial drivers

So what does ServiceNow, a company that deals mostly in enterprise automation software, get out of this? A “strong-performing model and a responsible AI model license that permits commercial use,” said Harm de Vries, the lead of the Large Language Model Lab at ServiceNow Research and the co-lead of the BigCode project.

One imagines that ServiceNow will eventually build StarCoder into its commercial products. The company wouldn’t reveal how much, in dollars, it’s invested in the BigCode project, save that the amount of donated compute was “substantial.”

“The Large Language Models Lab at ServiceNow Research is building up expertise on the responsible development of generative AI models to ensure the safe and ethical deployment of these powerful models for our customers,” de Vries said. “The open-scientific research approach to BigCode provides ServiceNow developers and customers with full transparency into how everything was developed and demonstrates ServiceNow’s commitment to making socially responsible contributions to the community.”

StarCoder isn’t open source in the strictest sense. Rather, it’s being released under a licensing scheme, OpenRAIL-M, that includes “legally enforceable” use case restrictions that derivatives of the model — and apps using the model — are required to comply with.

For example, StarCoder users must agree not to leverage the model to generate or distribute malicious code. While real-world examples are few and far between (at least for now), researchers have demonstrated how AI like StarCoder could be used in malware to evade basic forms of detection.

Whether developers actually respect the terms of the license remains to be seen. Legal threats aside, there’s nothing at the base technical level to prevent them from disregarding the terms to their own ends.

That’s what happened with the aforementioned Stable Diffusion, whose similarly restrictive license was ignored by developers who used the generative AI model to create pictures of celebrity deepfakes.

But the possibility hasn’t discouraged von Werra, who feels the downsides of not releasing StarCoder aren’t outweighed by the upsides.

“At launch, StarCoder will not ship as many features as GitHub Copilot, but with its open-source nature, the community can help improve it along the way as well as integrate custom models,” he said.

The StarCoder code repositories, model training framework, dataset-filtering methods, code evaluation suite and research analysis notebooks are available on GitHub as of this week. The BigCode project will maintain them going forward as the groups look to develop more capable code-generating models, fueled by input from the community.

There’s certainly work to be done. In the technical paper accompanying StarCoder’s release, Hugging Face and ServiceNow say that the model may produce inaccurate, offensive, and misleading content as well as PII and malicious code that managed to make it past the dataset filtering stage.