Key Takeaways

- The tail command in Linux displays data from the end of a file, making it useful for monitoring log files and showing recent additions.

- The introduction of systemd in some Linux distributions changed the format of system log files to a binary format, but many application-generated log files still use plain text format.

- In addition to displaying updates in real-time, tail can also be used to display a specific number of lines, work with multiple files, display lines from the start of a file, use byte offsets, and be combined with other commands through piping.

The Linux tail command displays data from the end of a file. It can even display updates that are added to a file in real-time. We show you how to use it.

Did systemd Kill tail?

The tail command shows you data from the end of a file. Usually, new data is added to the end of a file, so the tail command is a quick and easy way to see the most recent additions to a file. It can also monitor a file and display each new text entry to that file as they occur. This makes it a great tool to monitor log files.

Many modern Linux distributions have adopted the systemd system and service manager. This is the first process executed, it has process ID 1, and it is the parent of all other processes. This role used to be handled by the older init system.

Along with this change came a new format for system log files. No longer created in plain text, under systemd they are recorded in a binary format. To read these log files, you must use the journactl utility. The tail command works with plain text formats. It does not read binary files. So does this mean the tail command is a solution in search of a problem? Does it still have anything to offer?

There’s more to the tail command than showing updates in real-time. And for that matter, there are still plenty of log files that are not system generated and are still created as plain text files. For example, log files generated by applications haven’t changed their format.

Using tail on Linux

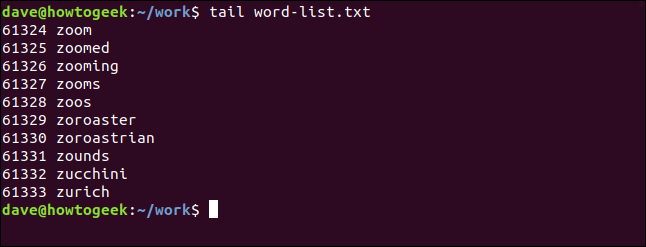

Pass the name of a file to tail and it will show you the last ten lines from that file. The example files we’re using contain lists of sorted words. Each line is numbered, so it should be easy to follow the examples and see what effect the various options have.

tail word-list.txt

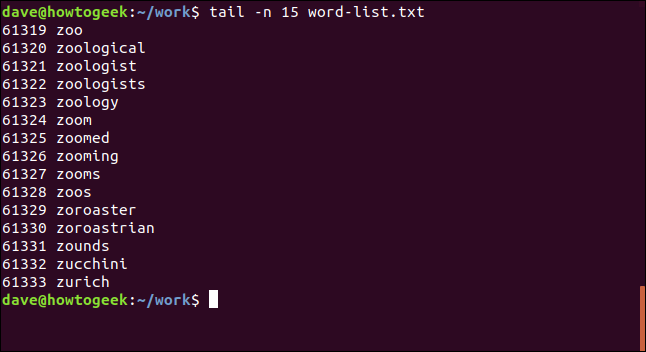

To see a different number of lines, use the -n (number of lines) option:

tail -n 15 word-list.txt

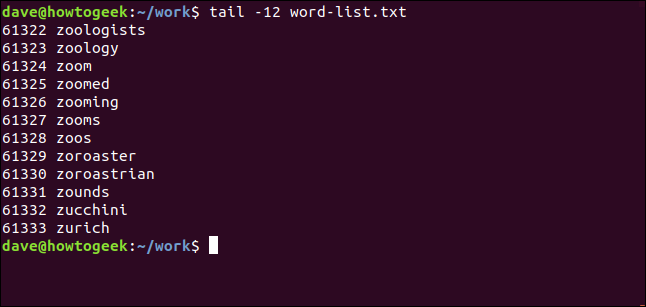

Actually, you can dispense with the “-n”, and just use a hyphen “-” and the number. Make sure there are no spaces between them. Technically, this is an obsolete command form, but it is still in the man page, and it still works.

tail -12 word-list.txt

Using tail With Multiple Files

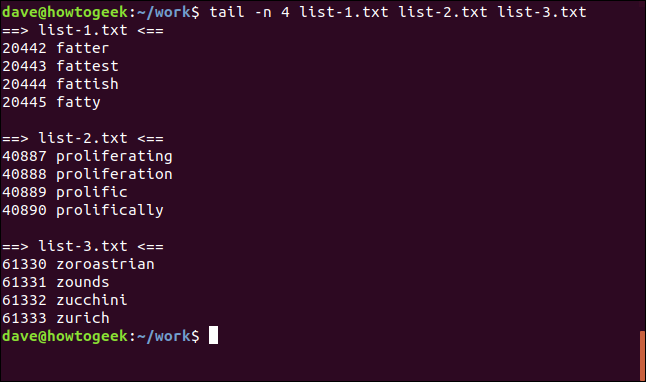

You can have tail work with multiple files at once. Just pass the filenames on the command line:

tail -n 4 list-1.txt list-2.txt list-3.txt

A small header is shown for each file so that you know which file the lines belong to.

Displaying Lines from the Start of a FIle

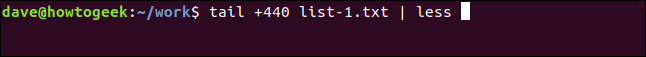

The + (count from the start) modifier makes tail display lines from the start of a file, beginning at a specific line number. If your file is very long and you pick a line close to the start of the file, you’re going to get a lot of output sent to the terminal window. If that’s the case, it makes sense to pipe the output from tail into less.

tail +440 list-1.txt

You can page through the text in a controlled fashion.

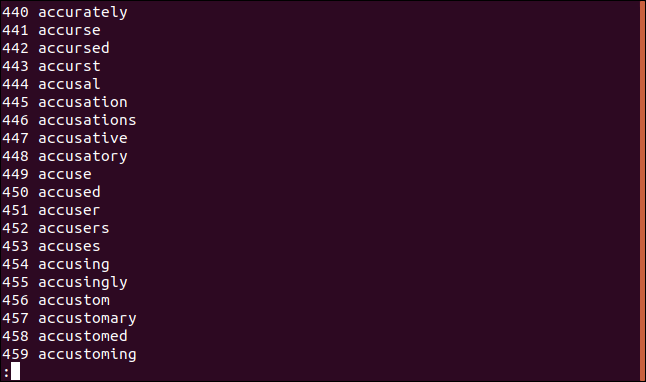

Because there happen to be 20,445 lines in this file, this command is the equivalent of using the “-6” option:

tail +20440 list-1.txt

Using Bytes With tail

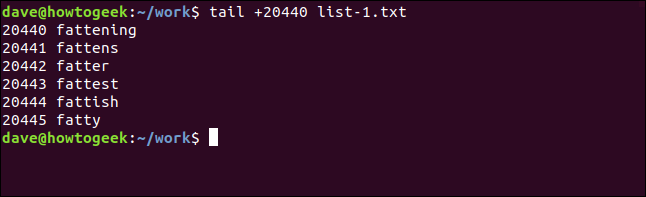

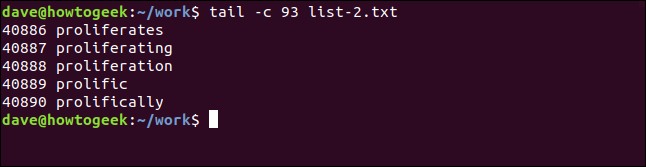

You can tell tail to use offsets in bytes instead of lines by using the -c (bytes) option. This could be useful if you have a file of text that was formatted into regular-sized records. Note that a newline character counts as one byte. This command will display the last 93 bytes in the file:

tail -c 93 list-2.txt

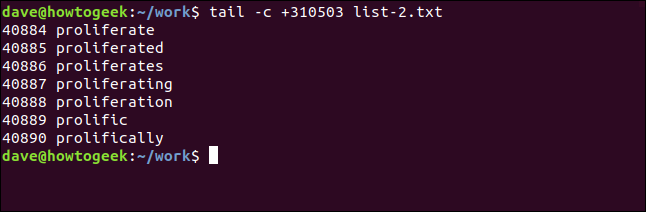

You can combine the -c (bytes) option with the + (count from the start of the file) modifier, and specify an offset in bytes counted from the start of the file:

tail -c +351053 list-e.txt

Piping Into tail

Earlier, we piped the output from tail into less . We can also pipe the output from other commands into tail.

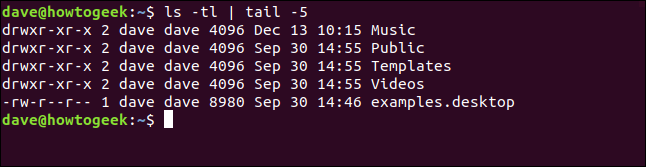

To identify the five files or folders with the oldest modification times, use the -t (sort by modification time) option with ls , and pipe the output into tail.

ls -tl | tail -5

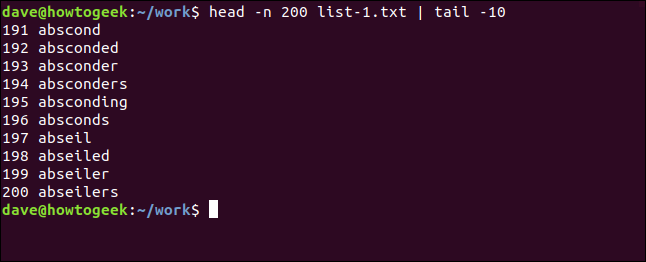

The head command lists lines of text from the start of a file. We can combine this with tail to extract a section of the file. Here, we’re using the head command to extract the first 200 lines from a file. This is being piped into tail, which is extracting the last ten lines. This gives us lines 191 through to line 200. That is, the last ten lines of the first 200 lines:

head -n 200 list-1.txt | tail -10

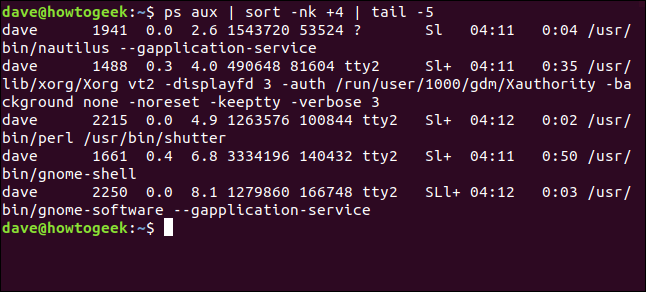

This command lists the five most memory-hungry processes.

ps aux | sort -nk +4 | tail -5

Let’s break that down.

The ps command displays information about running processes. The options used are:

- a: List all processes, not just for the current user.

- u: Display a user-oriented output.

- x: List all processes, including those not running inside a TTY.

The sort command sorts the output from ps . The options we’re using with sort are:

- n: Sort numerically.

- k +4: Sort on the fourth column.

The tail -5 command displays the last five processes from the sorted output. These are the five most memory-hungry processes.

Using tail to Track Files in Real-Time

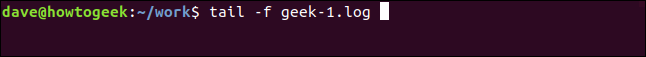

Tracking new text entries arriving in a file — usually a log file — is easy with tail. Pass the filename on the command line and use the -f (follow) option.

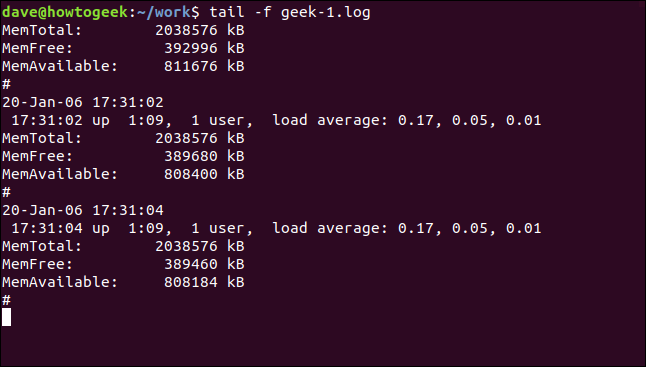

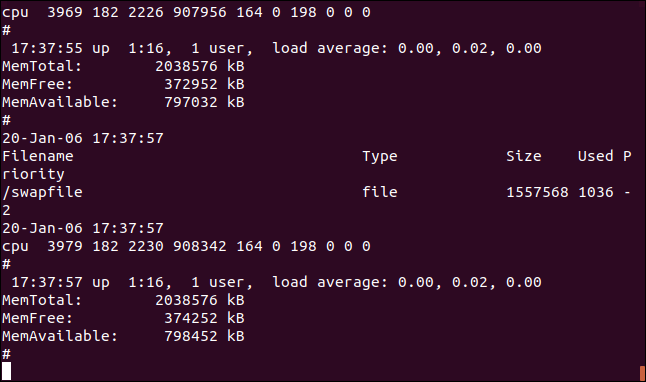

tail -f geek-1.log

As each new log entry is added to the log file, tail updates its display in the terminal window.

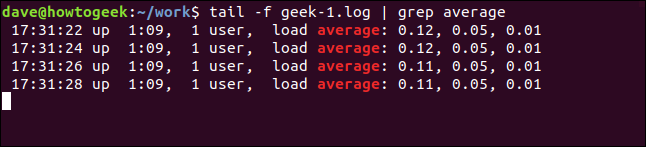

You can refine the output to include only lines of particular relevance or interest. Here, we’re using grep to only show lines that include the word “average”:

tail -f geek-1.log | grep average

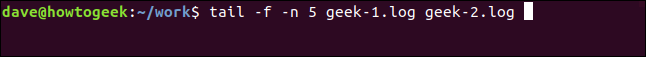

To follow the changes to two or more files, pass the filenames on the command line:

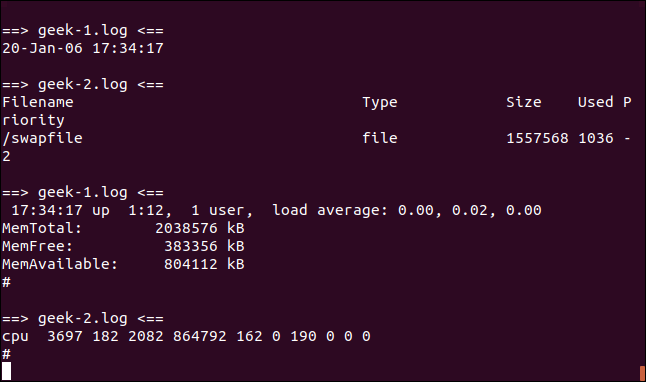

tail -f -n 5 geek-1.log geek-2.log

Each entry is tagged with a header that shows which file the text came from.

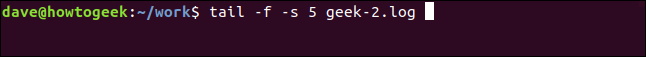

The display is updated each time a new entry arrives in a followed file. To specify the update period, use the -s (sleep period) option. This tells tail to wait a number of seconds, five in this example, between file checks.

tail -f -s 5 geek-1.log

Admittedly, you can’t tell by looking at a screenshot, but the updates to the file are happening once every two seconds. The new file entries are being displayed in the terminal window once every five seconds.

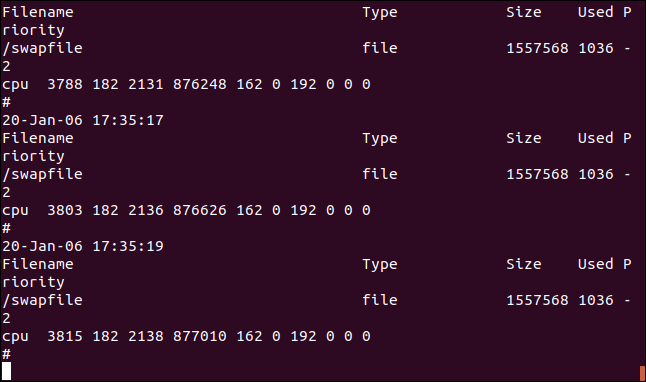

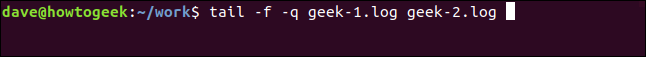

When you are following the text additions to more than one file, you can suppress the headers that indicate which log file the text comes from. Use the -q (quiet) option to do this:

tail -f -q geek-1.log geek-2.log

The output from the files is displayed in a seamless blend of text. There is no indication which log file each entry came from.

tail Still Has Value

Although access to the system log files is now provided by journalctl, tail still has plenty to offer. This is especially true when it is used in conjunction with other commands, by piping into or out of tail.

systemd might have changed the landscape, but there’s still a place for traditional utilities that conform to the Unix philosophy of doing one thing and doing it well.