Quick Links

- Why 12 Commands to List Devices?

Key Takeaways

- There are multiple commands to list devices in Linux, each with variations in content and detail, catering to different use cases and preferences.

- Most of these commands are already included in Linux distributions, but some installations may require additional commands like procinf, lsscsi, hwinfo, lshw, and hdparm.

- Run “sudo apt install hwinfo” on Ubuntu or “sudo dnf install hwinfo” on Fedora to install hwinfo, then run “hwinfo –short” to get a quick list of devices.

Find out exactly what devices are inside your Linux computer or connected to it. We’ll cover 12 commands for listing your connected devices.

Why 12 Commands to List Devices?

However many ways there are to skin a cat, I’d be willing to bet that there are more ways to list the devices that are connected to, or housed inside of, your Linux computer. We’re going to show you 12 of them. And that’s not all of them!

Inevitably, there’s a lot of overlap in the information that you can get out of these commands, so why bother describing this many of them?

Well, for one thing, the variations in content and detail make them sufficiently different that some people will prefer one method over another. The output format of one command might lend itself particularly well to a specific use case. The format of another command might be ideally suited to its being piped through grep, or another method of further processing.

Primarily though, it is to make the article as general as possible. Rather than decide which commands are going to be of interest or use to our readership, we’d rather provide a broad sample of the commands that are available and have our readers choose which ones they will use and which ones they will leave untouched.

Installation Required

Most of these commands are included within your Linux distribution by default. Ubuntu, Fedora, and Manjaro were used as a representative sample of distributions from the main branches of the Debian, Red Hat and Arch families.

All three distributions needed to install procinfo , which provides the lsdev command. The lsscsi command also needed to be installed on all three.

To install lsdev and lsscsi, use these commands.

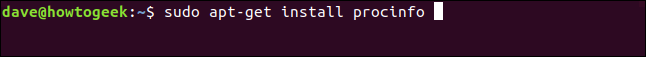

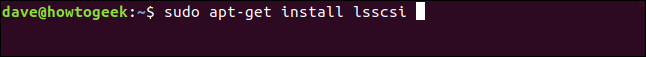

On Ubuntu:

sudo apt-get install procinf

sudo apt-get install lsscsi

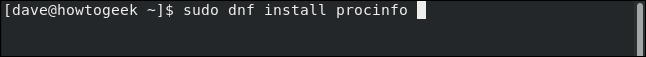

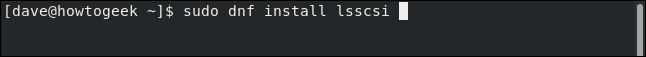

On Fedora:

sudo dnf install procinfo

sudo dnf install lsscsi

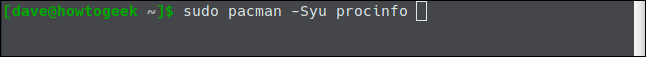

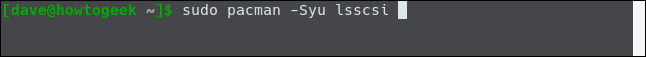

On Manjaro:

sudo pacman -Syu procinfo

sudo pacman -Syu lsscsi

Surprisingly, Manjaro — famous for being a bare-bones type of distribution — was the distribution that had most of the commands we’re going to look at pre-installed.

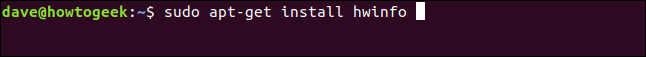

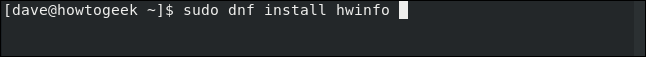

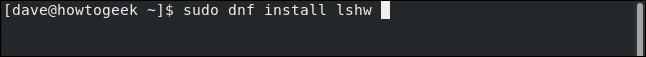

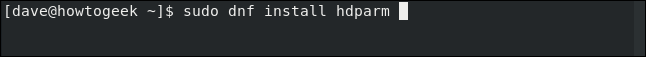

Ubuntu and Fedora needed hwinfo installing, and Fedora also required lshw and hdparm installing.

On Ubuntu:

sudo apt-get install hwinfo

On Fedora:

sudo dnf install hwinfo

sudo dnf install lshw

sudo dnf install hdparm

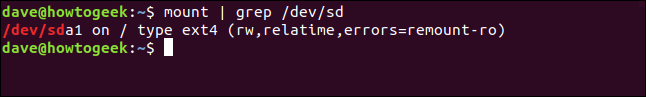

1. The mount Command

The mount command is used to mount filesystems.

But issuing the command with no parameters causes it to list all of the mounted filesystems, as well as the devices they are located on. So we can use this as a means of discovering those devices.

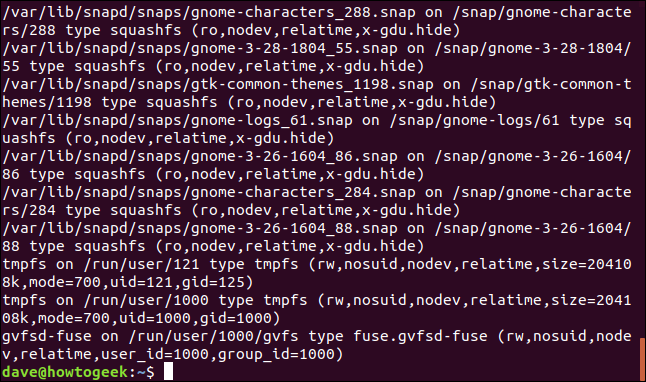

mount

The output from mount can be longer than you expected, especially if you have used the snap method to install software. Each time you use snap you acquire another pseudo-filesystem and these get listed by mount . Of course, these do not have physical devices associated with them, so they are just obscuring the real picture.

If you spot a real filesystem in the listing sitting on a hard drive, we can isolate it with grep.

Hard drives are identified by name, usually called “sd” followed by a letter starting at “a” for the first drive, “b” for the second drive and so one. Partitions are identified by adding a 1 for the first partition and 2 for the second partition, and so on.

So the first hard drive would be sda, and the first partition on that drive would be called sda1. Hard drives are interfaced through special device files (called block files) in /dev and then mounted somewhere on the filesystem tree.

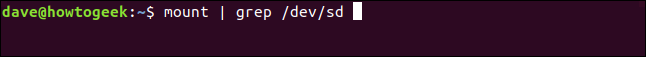

This command used grep to filter out the details of any drive that begins with “sd”.

mount | grep /dev/sd

The output contains the single hard drive in the machine that was used to research this article.

The response from mount tells us that drive /dev/sda is mounted at / (the root of the filesystem tree) and it has an ext4 filesystem. The “rw” indicates it has been mounted in read-write mode

Relatime is the scheme used by the file timestamp updating routines. The access time is not written to the disk unless either the modified time (mtime) or change time (ctime) of a file is more recent than the last access time, or the access time (atime) is older than a system-defined threshold. This greatly reduces the number of disk updates that need to take place for frequently accessed files.

The “errors=remount-ro” indicates that if there are sufficiently severe errors, the filesystem will be remounted in read-only mode.

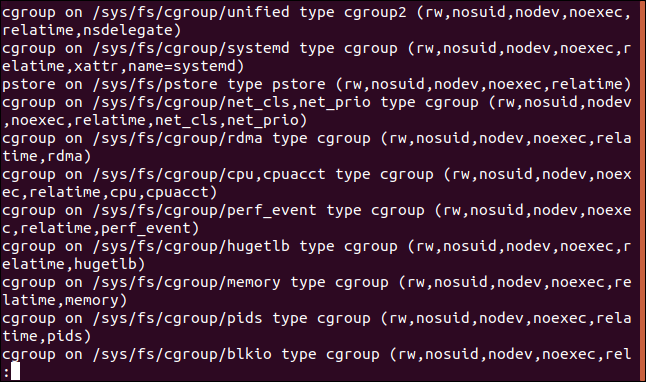

To be able to scroll through the output from mount and more easily spot the filesystems that are mounted on devices, pipe the output from mount through less .

mount | less

Scroll through the output until you see filesystems that are connected to /dev special files.

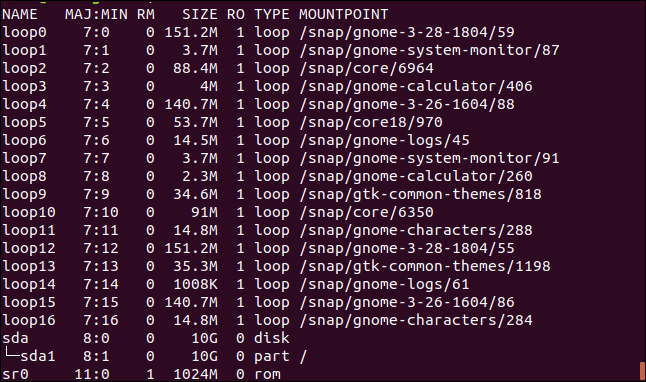

2. The lsblk Command

The lsblk command lists the block devices, their mount point, and other information. Type lsblk at a command line:

lsblk

The output shows:

- Name: the name of the block device

- Maj:Min: The major number shows the device type. The minimum number is the number of the current device out of the list of devices of that type. 7:4, for example, means loop device number 4.

- RM: Whether the device is removable or not. 0 means no, 1 means yes.

- Size is the capacity of the device.

- RM: Whether the device is read-only or not. 0 means no, 1 means yes.

- Type: The type of the device, for example, loop, dir (directory), disk, rom (CD ROM), and so on.

- Mountpoint: Where the filesystem of the device is mounted.

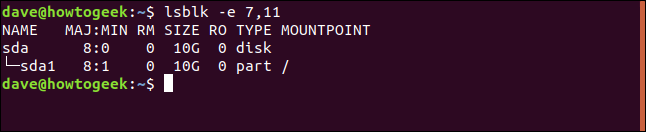

To de-clutter the output and remove the loop devices, we can use the -e (exclude) option and provide the number of the type of devices we wish to ignore.

This command will cause lsblk to ignore the loop (7) and cd room (11) devices.

lsblk -e 7,11

The results now only contain the hard drive sda.

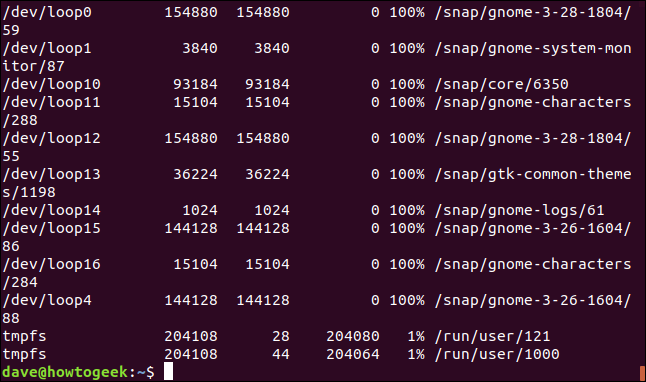

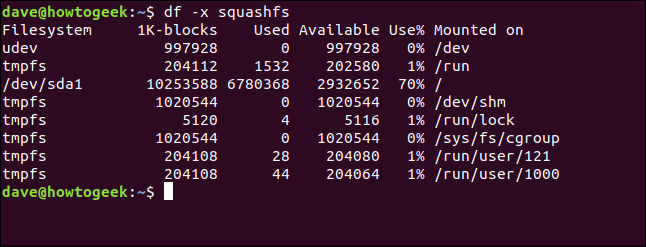

3. The df Command

The df command reports on drive capacities and used and free space.

Type df on the command line and press Enter.

df

The output table shows:

- Fileystem: The name of this filesystem.

- 1K-Blocks: The number of 1K blocks that are available on this filesystem.

- Used: The number of 1K blocks that have been used on this file system.

- Available: The number of 1K blocks that are unused on this file system.

- Use%: The amount of space used in this file system given as a percentage.

- File: The filesystem name, if specified on the command line.

- Mounted on: The mount point of the filesystem.

To remove unwanted entries from the output, use the -x (exclude) option. This command will prevent the loop device entries from being listed.

df -x squashfs

The compact output is much easier to parse for the important information.

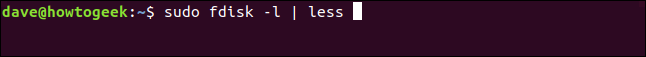

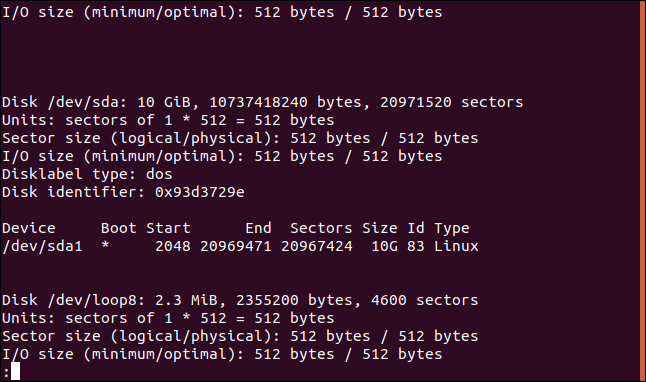

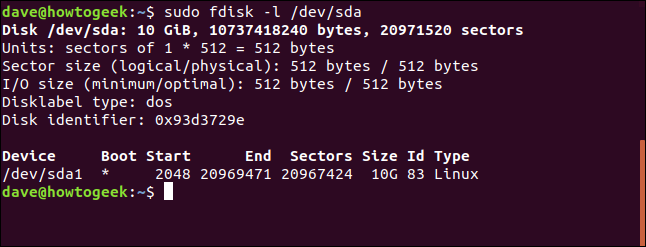

4. The fdisk Command

The fdisk command is a tool designed to manipulate the disk partition table, but it can be used to view information as well. We can use this to our advantage when we are investigating the devices in a computer.

We will use the -l (list) option to list the partition tables. Because the output might be very long, we will pipe the output from fdisk through less. Because fdisk has the potential to alter disk partition tables, we must use sudo.

sudo fdisk -l | less

By scrolling through less you will be able to identify the hardware devices. Here is the entry for hard drive sda. This is a physical hard drive of 10 GB.

Now that we know the identity of one of the hardware devices we can ask fdisk to report on that item alone.

sudo fdisk -l /dev/sda

We get an output of considerably reduced length.

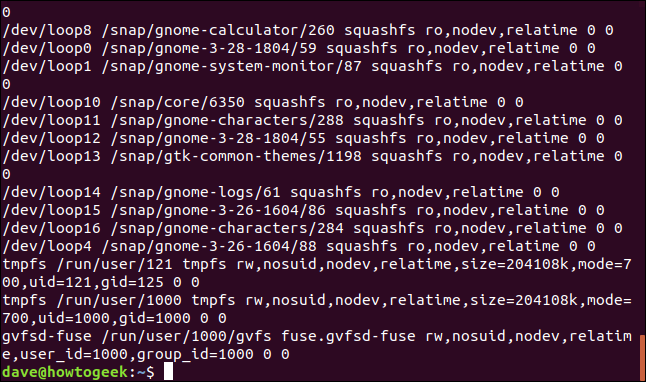

5. The /proc Files

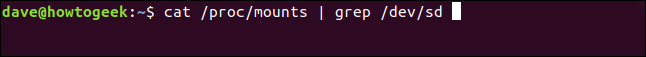

The pseudo-files in /proc can be viewed to obtain some system information. The file we will look at is /proc/mounts, which will give us some information regarding the mounted filesystems. We will use nothing grander than cat to view the file.

cat /proc/mounts

The listing shows the special device file in /dev that is used to interface to the device and the mount point on the filesystem tree.

We can refine the listing by using grep to look for entries with /dev/sd in them. This will filter out the physical drives.

cat /proc/mounts | grep /dev/sd

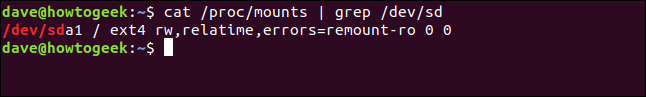

This gives us a much more manageable report.

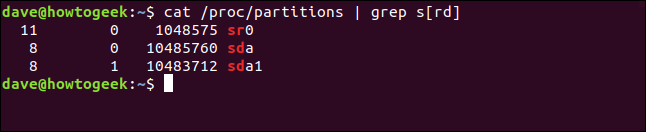

We can be slightly more inclusive by using grep to look for devices that have /dev/sd and /dev/sr special device files. This will include hard drives and the CD ROM for this machine.

cat /proc/partitions | grep s[rd]

There are now two devices and one partition included in the output.

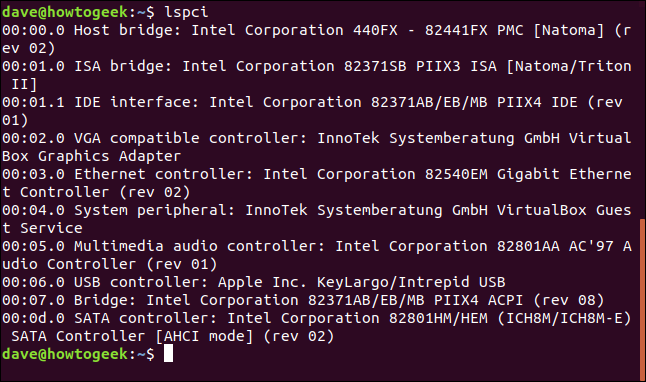

6. The lspci Command

The lspci command lists all of the PCI devices in your computer.

lspci

The information provided is:

- Slot: The slot the PCi device is fitted in

- Class: The class of the device.

- Vendor name: The name of the manufacturer.

- Device name: The name of the device.

- Subsystem: Subsystem vendor name (if the device has a subsystem).

- Subsystem name: If the device has a subsystem.

- Revision number: The version number of the device

- Programming interface: The programming interface, if the device provides one.

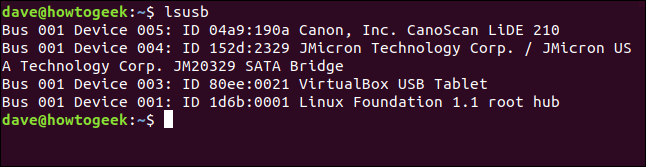

7. The lsusb Command

The lsusb command will list devices that are connected to USB ports on your computer as well as USB enabled devices that are built into your computer.

lsusb

This test computer has a Canon scanner attached to it as USB device 5, and an external USB drive as USB device 4. Devices 3 and 1 are internal USB interface handlers.

You can receive a more verbose listing by using the -v (verbose) option, and even more verbose version by using -vv.

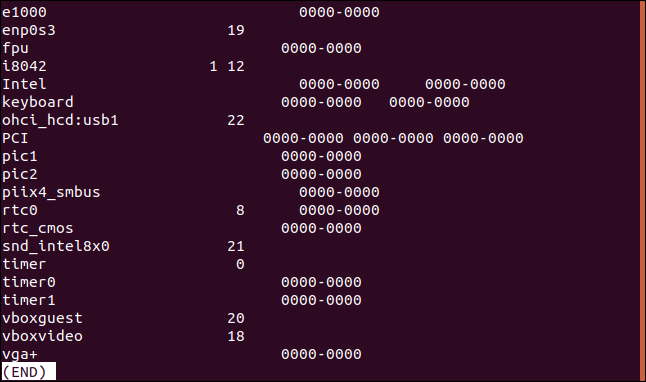

8. The lsdev Command

The lsdev command displays information on all of the installed devices.

This command generates a lot of output, so we’re going to pipe it through less.

lsdev | less

There are many hardware devices listed in the output.

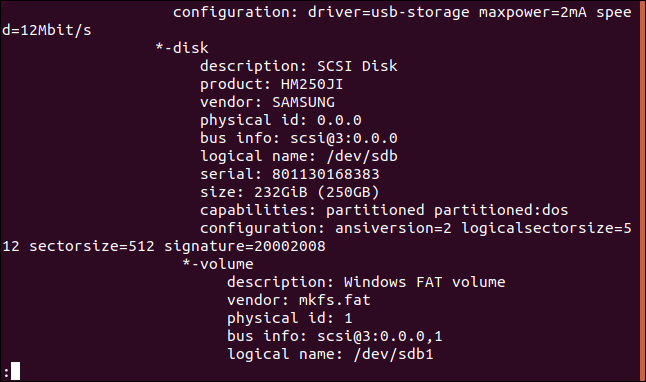

9. The lshw Command

The lshw command lists the devices connected to your computer. This is another command with a lot of output. On the test computer, there were over 260 lines of information generated. We’ll pipe it through less once more.

Note that you need to use sudo with lshw to get the most out of it. If you don’t, it won’t be able to access all devices.

sudo lshw | less

Here is the entry for the CD ROM with a SCSI interface. As you can see the information provided for each device is very detailed. lshw reads most of its information from the various files in /proc.

If you want a shorter, less detailed output, you can use the --short option.

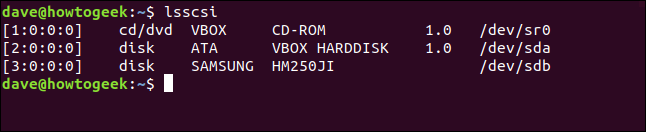

10. The lsscsi Command

As you would imagine by now, the lsscsi command lists the SCSI devices connected to your computer.

lsscsi

Here are the SCSI devices connected to this test machine.

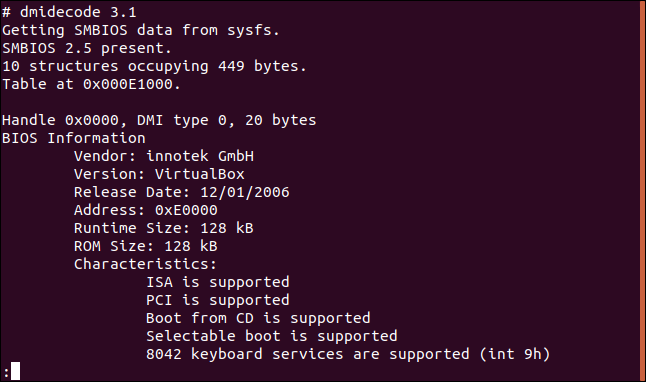

11. The dmidecode Command

The dmidecode commands decodes the Desktop Management Interface (DMI) tables, and extracts information related to the hardware connected to the computer, and inside the computer.

The DMI is also sometimes referred to as the SMBIOS (the System Management Basic Input/Output System) although they are really two different standards.

Again, we’ll pipe this through less.

dmidecode | less

The dmidecode command can report on over 40 different hardware types.

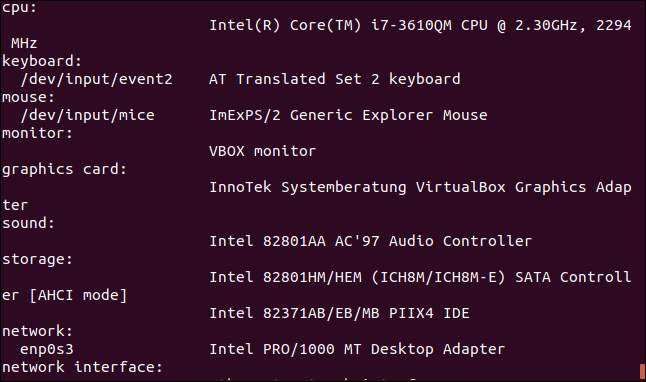

12. The hwinfo Command

The hwinfo command is the most verbose of them all. When we say that you need to pipe something through less, this time it isn’t optional. On the test computer, it generated 5850 lines of output!

You can start things off gently by including the --short option.

hwinfo --short

If you really need to see the finest-grained detail, repeat this and omit the --short option.

Wrap It Up

So, here’s our dozen ways to investigate the devices within, or attached to, your computer.

Whatever your particular interest in hunting down this hardware may be, there’ll be a method in this list that will enable you to find what you need.