You might think that connecting anonymously to a public Wi-Fi network doesn’t reveal much about you. You might be using a VPN (virtual private network) to protect everything you do. But even if you aren’t, the vast majority of websites and email servers (and pretty much all those run by companies) use client-to-server encryption. But what if you could be tracked anyway?

Apple has a solution for this as it does for many tracking systems. The company’s trick lies in how Wi-Fi (and ethernet) adapters identify themselves over a local network when connecting wirelessly or via an ethernet cable. Every network adapter has a factory-assigned unique address baked in at the time of manufacture. It’s called a Media (or Medium) Access Control address; the abbreviation is MAC, confusingly enough, but it has nothing to do with Macintoshes.

Where an IP (Internet Protocol) address defines your machine’s location on the internet, a MAC address defines it on your local area network (LAN). The MAC is in part how devices on a LAN all communicate with one another, whether over Wi-Fi or ethernet.

Apple recognized that any fixed identifier could be used to track someone if it were tied to records captured beyond the local network. When you connect to a wireless hotspot, your Wi-Fi MAC address gets transmitted because it’s part of that connection. If that MAC address doesn’t change over time, the backend of a hotspot portal could build up a profile of you (or your device) using a variety of clues that includes any Bluetooth broadcasts, credit cards you use at a retail location, and other network and broadcast identifiers that only prove trackable when paired with a fixed network ID.

While a MAC address is factory assigned, it’s not necessarily immutable. For instance, you may have had the experience of connecting to a Wi-Fi gateway and seeing an option buried in advanced settings to modify the MAC address. (This can sometimes be helpful when you’re replacing a router, and your ISP’s broadband modem or adapter is registered to that older device’s MAC address.)

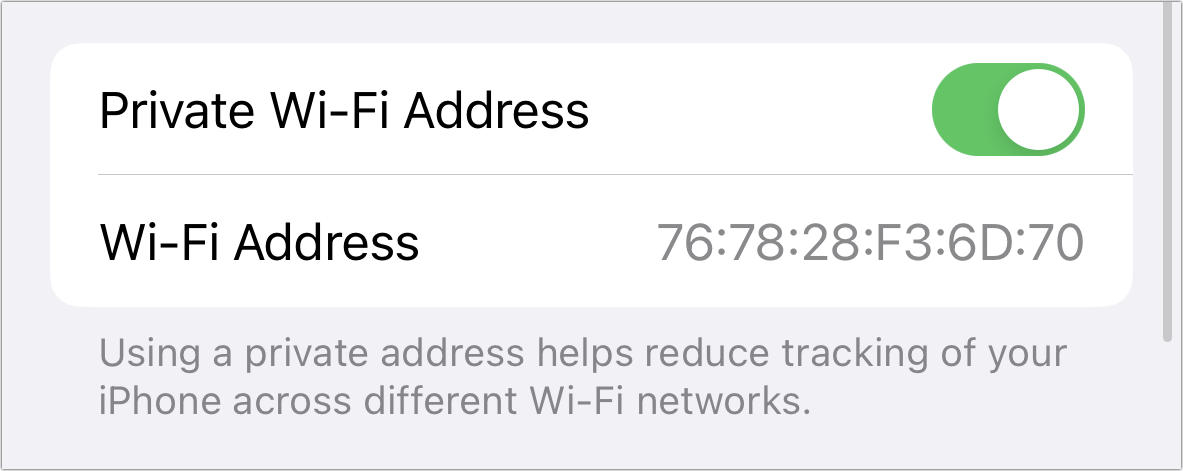

The ability for a MAC to change and the potential for a fixed Mac to be tracked is why Apple introduced Private Wi-Fi Address as a feature nearly three years ago in iOS 14, iPadOS 14, and watchOS 7. It’s enabled by default. You can view the setting only for individual networks:

- On an iPhone or iPad, go to Settings > Wi-Fi and tap the i (info) icon for the active network. Starting in iOS 16/iPadOS 16, you can also tap Edit at the top of Wi-Fi settings and tap the i icon to view or change the Private Wi-Fi Address option for that network.

- On a Watch, go to Settings > Wi-Fi, tap the name of the network, and the Private Address setting appears.

With Private Wi-Fi Address enabled, your operating system invents a MAC address for every network you join and uses that address for that network unless and until:

- Six weeks has passed since the last time you joined the network with that device.

- You rejoin a network more than two weeks after you used the Forget This Network option for that network.

- You erase the device’s settings to reset your network settings (in iOS 15 or later: Settings > General > Transfer or Reset iPhone/iPad > Reset > Reset Network Settings; in iOS 14 or earlier: Settings > General > Reset > Reset Network Settings.)

(You might ask: what if Apple generates a MAC address already in use? The number of possible addresses is vast–over 280 trillion possibilities–and unlike a global IP address, it only needs to be unique on the local network.)

There’s no particular reason to disable this privacy feature unless you want to have a persistent MAC address for a personal or work network; some networks control access or assign IP addresses based on a MAC address, and ensuring the MAC address remains static could be helpful. You might also disable it if you think you’re experiencing problems with a hotspot network that keeps losing your login. I’ve seen this with airplane Wi-Fi and haven’t yet diagnosed whether it’s an issue with the airplane’s authentication system or private MAC addressing.

This Mac 911 article is in response to a question submitted by a Macworld reader.

Ask Mac 911

We’ve compiled a list of the questions we get asked most frequently, along with answers and links to columns: read our super FAQ to see if your question is covered. If not, we’re always looking for new problems to solve! Email yours to [email protected], including screen captures as appropriate and whether you want your full name used. Not every question will be answered, we don’t reply to email, and we cannot provide direct troubleshooting advice.