Our energy production is undergoing a much-needed transformation. This Monday, according to the German Federal Network Agency, 64% of electricity in the country was generated from renewable sources—about 15% more than last year. That’s good news, but it’s also a challenge. Because renewable energy sources have a big problem that they cannot be controlled.

For example, we can simply dump more fuel into a fossil-fuel power plant as needed, and we get more electricity. But sun and wind cannot be controlled; at best, they can be predicted for a few hours or days.

This in turn means that instead of adjusting energy production to consumption at peak times, as we have done in the past, we now have to adjust energy consumption to availability. Here, the smart home is a very big building block—and there is still endless work to be done.

Of course, energy sources in the US are very different than in Europe, with a mix of around 60% for fossil fuels, and around 21.5% for renewables in 2022. And the share varies a lot according to each state, some of which are as big as a European country.

We need variable electricity tariffs

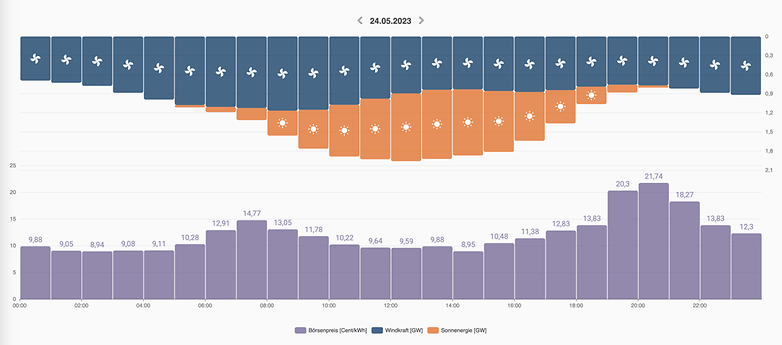

In Germany, electricity is traded on the EEX energy exchange in Leipzig; the prices, which vary by the hour, are determined in an auction at 12:00 noon on the previous day and announced from 12:40 onwards. The greater the share of renewable energies, the greater the fluctuations. We have to take advantage of this.

The concept is known in the US as time-of-use (TOU) and is enabled by smart meters, but the option is only available from a limited number of utility providers in select states in the US.

On the other side of the pond, however, there are already several providers of variable electricity tariffs, for example, the Berlin-based start-up Tibber. Here, customers pay a monthly base price, and all other costs are passed on directly—taxes, network fees, and so on are added to the actual EEX exchange price.

Such a tariff is the simplest and most direct way to get everyone involved. By rewarding energy consumption at the right time, it can be controlled—because if you participate, you can save a lot of money.

The possibilities are endless. Whether the smart dishwasher switches on automatically during the day at the most convenient time, the electric car fills up the battery as cheaply as possible, or the heat pump heats up the well-insulated domestic hot water tank at the right time. It’s all just a question of control.

But there is a second aspect that offers just as much potential: You can draw power from any outlet—and also feed it back into the home grid through any outlet via a grid-synchronized inverter. Batteries at home could therefore be filled up at favorable times, and the electricity could then be fed into the home grid at high-priced times and used instead of the expensive grid electricity. Of course, there is some conversion loss here from AC to DC and back to AC. But typically, the efficiency of good inverters for a round trip through the battery is around 80%.

Theoretically, cheaply purchased electricity could even be fed back into the power grid via the house grid, ideally of course when the grid has an energy demand or the energy price is high. This is already possible with solar cells or home energy storage systems. And with bi-directional charging in electric cars, some people are already using EVs as a home backup battery for the grid, even with the risk of voided warranties.

Just to give a rough idea of the potential: At the beginning of 2023, the number of e-cars on the German market will have broken the 1-million barrier. If we assume an average battery capacity of 65 kWh, we end up with a total of 65 GWh. Just for comparison: Germany’s largest pumped storage power plant, Goldisthal, has a capacity of “only” 1 GWh. So the dimensions are enormous, even if e-car users only make a small proportion of their car battery available in order to always maintain sufficient range.

Even the power stations that have been so popular in recent years could be made available to the grid as storage. Thanks to increasingly widespread LiFePO4 technology, modern power stations can easily withstand a decade of daily charging and discharging—and could even earn the user money as part of a decentralized buffer storage system. All it would take is a battery inverter like the EcoFlow PowerStream to feed the stored electricity not only into the home grid but also into the power grid.

The startup Daylight.eco has exactly such a product in mind. In late summer of this year, the startup plans to launch a battery on the German market that does nothing but refuel cheaply and then feed the electricity back into the home grid later. Like a balcony power plant, the purchase is expected to pay for itself in just a few years, saving the user money and at the same time relieving the strain on the grid.

The big problem: There is a lack of standards

So what stands in the way of a grid that regulates itself smartly as a whole? We need the appropriate hardware across the board—in other words, at least digital electricity meters that, if necessary, log consumption on an hourly basis via an additional gadget like the Tibber Pulse. Unfortunately, the smart meters currently installed in the US, for example, vary a lot in terms of supported protocols, interoperability, and, as usual, regulatory issues.

Better than a pure consumption meter, however, would be area-wide two-way meters, such as those that have long been mandatory for owners of solar systems. They would not only allow the consumption to be measured precisely but also feed-in—and the latter would of course be remunerated accordingly.

Instead of a fixed feed-in tariff, we also need—just as with consumption tariffs—a variable feed-in tariff that makes the purchase of bidirectional wall boxes or power stations capable of feeding electricity into the grid—and thus a dynamic relief of the power grid—attractive.

But there is still a lot of red tape on the way there, with even European countries still struggling with bureaucracy to regulate feed-in rules. In the US, feed-in tariff rules change a lot on the state level, with most bills targeting bigger installations, not homeowners.

If we want to create something really big—and that is the energy transition—then everyone has to participate; and it is up to the government to encourage and enable everyone to participate. Dynamic electricity tariffs will become more widespread in Germany in the near future, and we need ways to take full advantage of them. Above all, the bureaucratic hurdles need to be lowered.

At any rate, thanks to the German government’s current PV strategy, some progress will be made on the bureaucratic hurdles in the near future, especially with regard to plug-in solar systems and balcony power plants. But all these are only the first steps and not yet the goal. There is still a long way to go, and we all have to take small steps together—and we at NextPit want to be part of it.