The idea to write this article was sparked when I received a press release from Fairphone a few weeks ago. The latter announced that the Fairphone 3 (review) and Fairphone 3+, launched in 2019 and 2020, respectively, would go from Android 11 to Android 13, skipping Android 12 in the process. And that, in the absence of official support from the chip manufacturer (Qualcomm), Fairphone would have to perform this operation internally.

That said, this fact sparked my curiosity as I wanted to figure out how all of this works. What kind of support can an SoC manufacturer provide to a smartphone manufacturer when it comes to software maintenance? Most importantly, if that level of support expires, how can a manufacturer take on this cumbersome process of rolling out Android updates themselves?

Interviews are good, especially when you talk to someone who really knows his or her stuff. This is the case with Agnes Crepet who gave me a very interesting overview of the steps a manufacturer like Fairphone has to go through to deploy an Android update.

But she also gave me some hope, revealing avenues that could, in time, anchor sustainability in our purchasing behaviors, but also when it comes to the commercial strategies of manufacturers.

“It’s long, it’s expensive, it’s complex.”

As a smartphone manufacturer, you have to go through a number of steps before you can roll out an Android update. This is logical. But I’m not going to give you a Wikipedia entry on how an Android update works.

No, the point of understanding this process is to see that it’s not an impossible task that even John Wick cannot complete. If Fairphone can do it over a long period of time, major players in the market like Samsung or Xiaomi, with colossal resources at their disposal, can as well.

I’ll come back to that below. In the meantime, the entire process can be summarized in four main steps:

- The release of the new AOSP public version by Google.

- Preparation of the code baseline by the chipset vendor and its implementation by the smartphone manufacturer.

- Compliance with the requirements of mobile operators.

- Android certification by Google, followed by network certification by the operators.

It all begins with Google and the new version of Android. The smartphone manufacturer is normally supported by the chip supplier of its model.

In the case of Fairphone, it would be Qualcomm since the Fairphone 3 and Fairphone 3+ are powered by the Snapdragon 750 SoC. Fairphone and Qualcomm, therefore, would have negotiated at the time of the chipset’s purchase on a certain duration for this support, where the end of life would have been fixed in advance.

This leads us to the second step. As part of this support, Qualcomm will create a new baseline (the source code, to put it bluntly) and adapt it to the new AOSP version before providing it to Fairphone.

This process can be a lengthy or short period, depending on whether the chip is more or less high-end and therefore the priority level differs in the eyes of Qualcomm.

Testing, certification, and more testing

Once the new baseline is handed down, Fairphone can begin implementing it on its devices.

“As a manufacturer, I can start to port this to my device with potentially some drivers to rewrite, with some adaptation to do on the hardware. The camera is one such example. We work with different cameras, and we have to do what we call the bringer, to readapt the baseline to the whole of our phone,” explained Agnes.

She continued: “From there, we have to make sure that we meet all the requirements of the mobile operators. Each operator has its own requirements and the details are not made public. It’s a very complicated affair. You have to make sure there’s no regression from Android 12 to Android 13, for example, and if there is, you will be tasked with implementing the upgrades.”

To make sure that everything runs smoothly on the network level, major test campaigns are being carried out all over Europe with professional testers everywhere.

If everything is ok, two types of approvals are still needed: certifications from Google and from the operators.

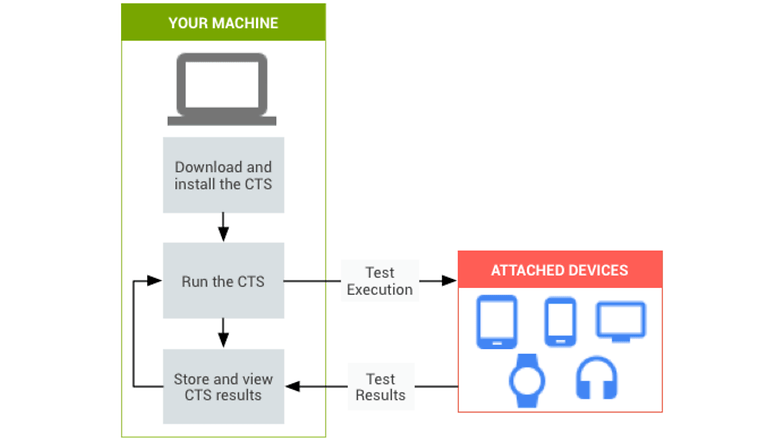

“The first is Google. We send everything to a Google certifying body that submits the update to a test suite called CTS (Compatibility Test Suite). That’s hundreds of thousands of tests. If just one fails, you don’t have Android certification and you can’t deploy the update.”

“If Google’s certifying body says it’s good, you then proceed to carrier tests. You have to go through one European operator after another, the biggest ones being the most demanding. And only after that can you ‘ship’ the update. If one thing crashes, it’s back to square one. It’s long, it’s expensive, it’s complex.”

The end of chip support is not fatal

What I just described thanks to Agnes Crepet’s explanations is the “classic” process when the smartphone manufacturer still has official support from the chip provider.

“But the chip support is just one aspect among many to take into consideration,” Agnes added, “When you don’t have support anymore, you can simply go through AOSP without the baseline. And it’s still possible to do things with the chipset vendor, for a fee.”

The expert explained to me that “when we bought the chipset for the Fairphone 3 (a Snapdragon 750), we knew when the support was going to end pretty much shortly afterward, and on some chipsets, if plenty of manufacturers bought and incorporated it (which was not the case with the SD 750), you can get a nice surprise and get a support extension.”

“Qualcomm is making more and more of an effort to make sure that even for non-flagships, the support level is adequate. And there is some transparency on this, so we don’t blame the chipmaker.”

According to Agnes, the fact that Fairphone is pushing for software maintenance beyond official support, at its own expense, mostly to show that it’s possible.

It’s super expensive, it’s risky, so that’s why not all manufacturers do it, and it’s much more complicated for Fairphone. We have fewer resources, I have five people on my team, so it’s more critical for us.”

Admittedly, Fairphone doesn’t have many models in its catalog compared to Samsung or Xiaomi, the expert concedes. “But at some of the big manufacturers, there is sometimes not a single model that is updated as long as our smartphones.”

“We don’t focus on the right criteria.”

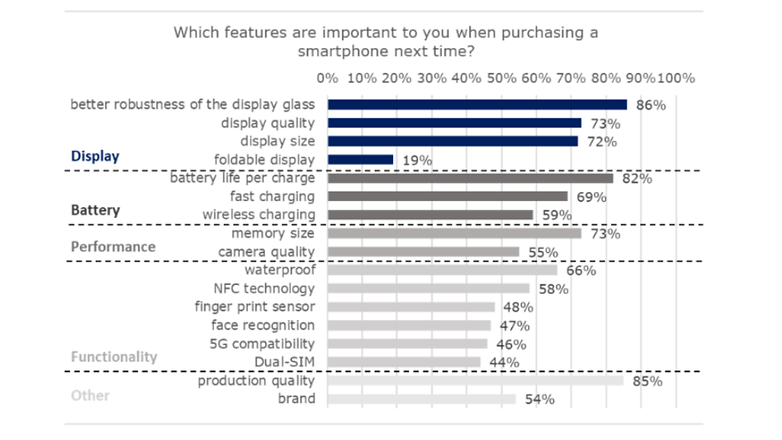

From my perspective as a journalist, I know that software durability is becoming an increasingly important purchasing criterion. Personally, I look into this matter. But with each new product launch, I miss seeing manufacturers who are sorely lacking in clarity and transparency about their update policies.

If I want to know how many updates a Xiaomi device will receive, I don’t have any resources or official documentation to find this information. Samsung plays the role of the industry leader with a more or less exhaustive list of models and their update cycles. But it does not specify the frequency and especially the decrease in frequency of its security patches over time.

There is this preconception that users throw away their smartphone after using it for two years. Manufacturers take advantage of this idea, which is not necessarily proven, as an argument to justify their lack of software updates.

However, this is more a result than a cause. Angès shared with me the preparatory study for the European Ecodesign Directive which aims to limit the waste of electronic products and ensure a better sustainability in the consumption of these products. She represents Fairphone in the government working group for the implementation of this directive in France.

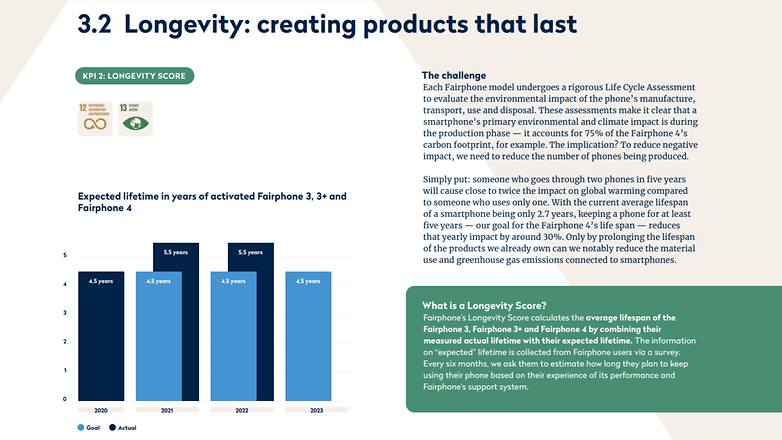

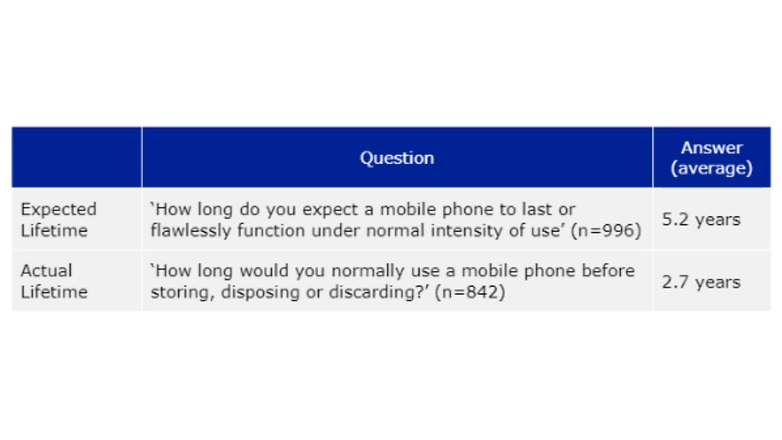

In this study, one of the surveys conducted shows that 19% of European consumers said they bought a new smartphone because the software was no longer receiving any updates or support. Another barometer showed that on average, consumers would like to keep the same smartphone for 5.2 years. Reality showed otherwise, with owners parting with their handsets after a mere 2.7 years.

“Marketing pushes consumers to buy a new phone and we are not interested in the right criteria,” lamented Agnes, who was far from feeling resigned.

“Upcoming European regulations will impose minimum requirements. The Ecodesign directive, for example, stipulated that manufacturers must respect a commitment of five years of security updates and three years of operating system updates.”

“But some European labels, like the German Blue Angel ecolabel, require a minimum of seven years of security updates and three years of operating system updates.”

And that, as Agnes reminded me, is AFTER sales of the smartphone end. So if you sell a smartphone in 2023 over three years, following Fairphone’s model, you’ll have to keep it updated for five years after sales have stopped in 2026.

Another hopeful path is the integration of software longevity into the reparability index. This index was implemented in France in 2021 as part of the anti-waste law which will be the durability index and take software support into account as part of its criteria.

“You have cultural obsolescence, but that doesn’t concern the extreme majority of people. There are people who want to keep their smartphone for a longer period of time but they are forced to buy a new one simply because the banking app doesn’t work anymore, TikTok [smile] doesn’t work anymore, and the interface is a little slower.”

Finally, a last track toward greater durability could be the unlockability of the bootloader. The ability on any smartphone to install an alternative OS once the manufacturer’s official support has expired.

There are a lot of very credible alternatives, supported by very active communities. /e/OS, postmarketOS, Ubuntu Touch are among the most notable examples that Agnès Crepet suggested.

In any case, Fairphone wants to set an example and above all encourage, even inspire, other manufacturers to make more efforts in terms of software sustainability. This philosophy meets, in my opinion, a real need and desire of consumers. A desire which manufacturers like Samsung, Xiaomi, and the other industry players will have to align themselves.

However, without the entire legislative branch at the European Union level working together, Angès Crepet does not believe that there will be much awareness. While waiting for the legislative apparatus to be put in place, it is also up to us to change our purchasing behavior. It is also up to me, as a tech journalist and reviewer, to integrate sustainability more significantly into my evaluation criteria.

In any case, it’s a fascinating topic that I’d be happy to explore further for our readers. Would you be interested? I would love to test some alternative OSes out, and I’m also interested in repairability guides. What do you think about it?